The way forward

The current crisis

The region’s economy is thriving. After the deep recession of the late 1980s and early 1990s, and the financial crisis of 2008–2009, the tri-state area bounced back. People are choosing to live, work, and visit here. New York City is now one of the safest big cities in the nation. Public health has improved, as has quality of life.

National and global trends towards urbanization have played a part in this renaissance, but intentional policy choices, such as major investment programs in both housing and transit in the 1980s and 1990s, also positioned New York to capitalize on these trends.

But this recent economic success is not guaranteed, and past development trends teach us that growth alone does not always benefit everyone.

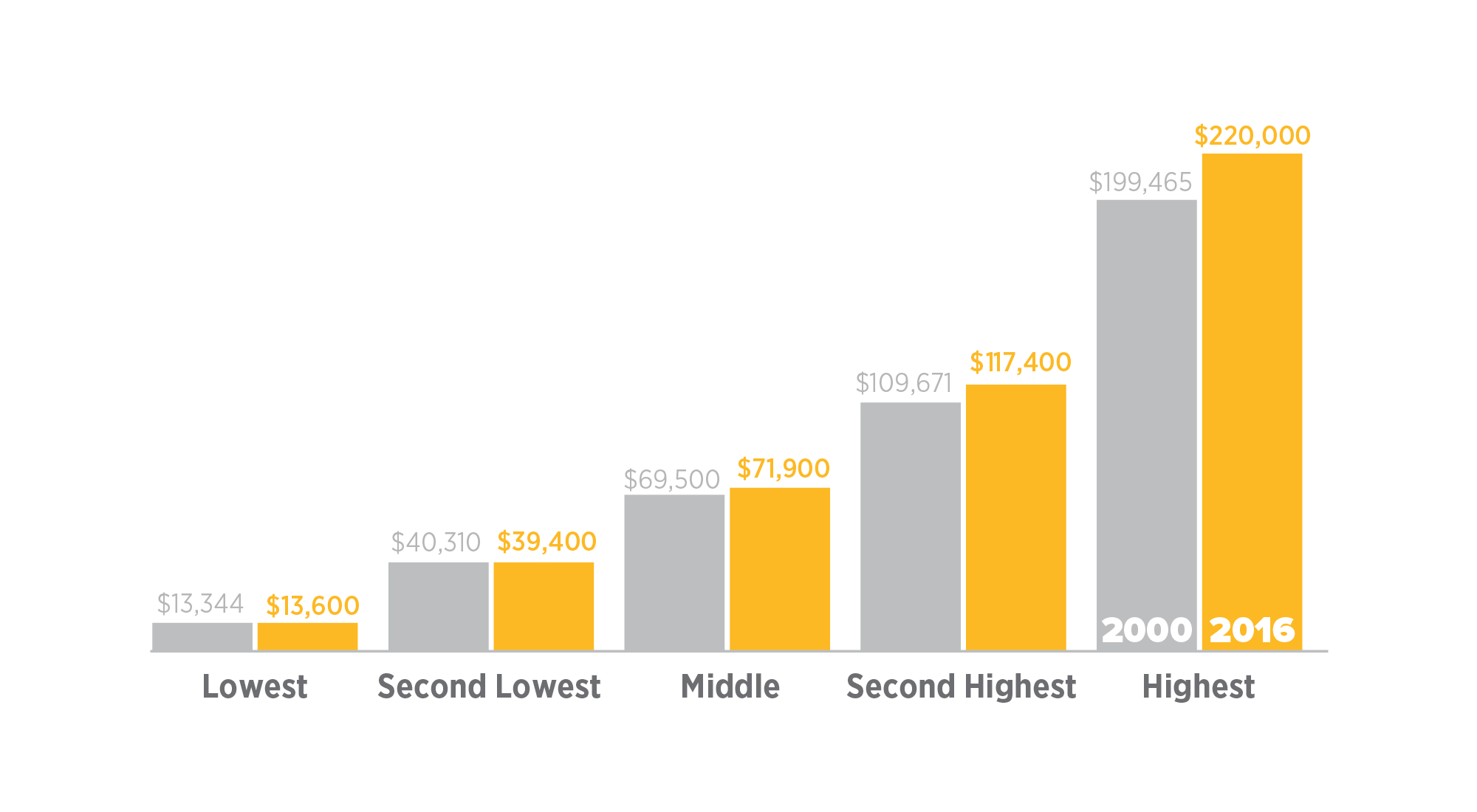

For the bottom three-fifths of households, incomes have stagnated since 2000. More people live in poverty today than a generation ago. Those in the middle have fewer good job opportunities and chances to climb the economic ladder. There is greater income inequality in the region than elsewhere in the country.

While household incomes have plateaued, housing costs have risen sharply and are taking a larger share of household budgets. For many people, discretionary income cannot cover critical expenses such as health care, college, child care, and food.

When it becomes too expensive to live here, talented people pick up and leave for more affordable places. It’s no coincidence that peak real estate prices in the mid-2000s coincided with the highest recent level of outward migration.

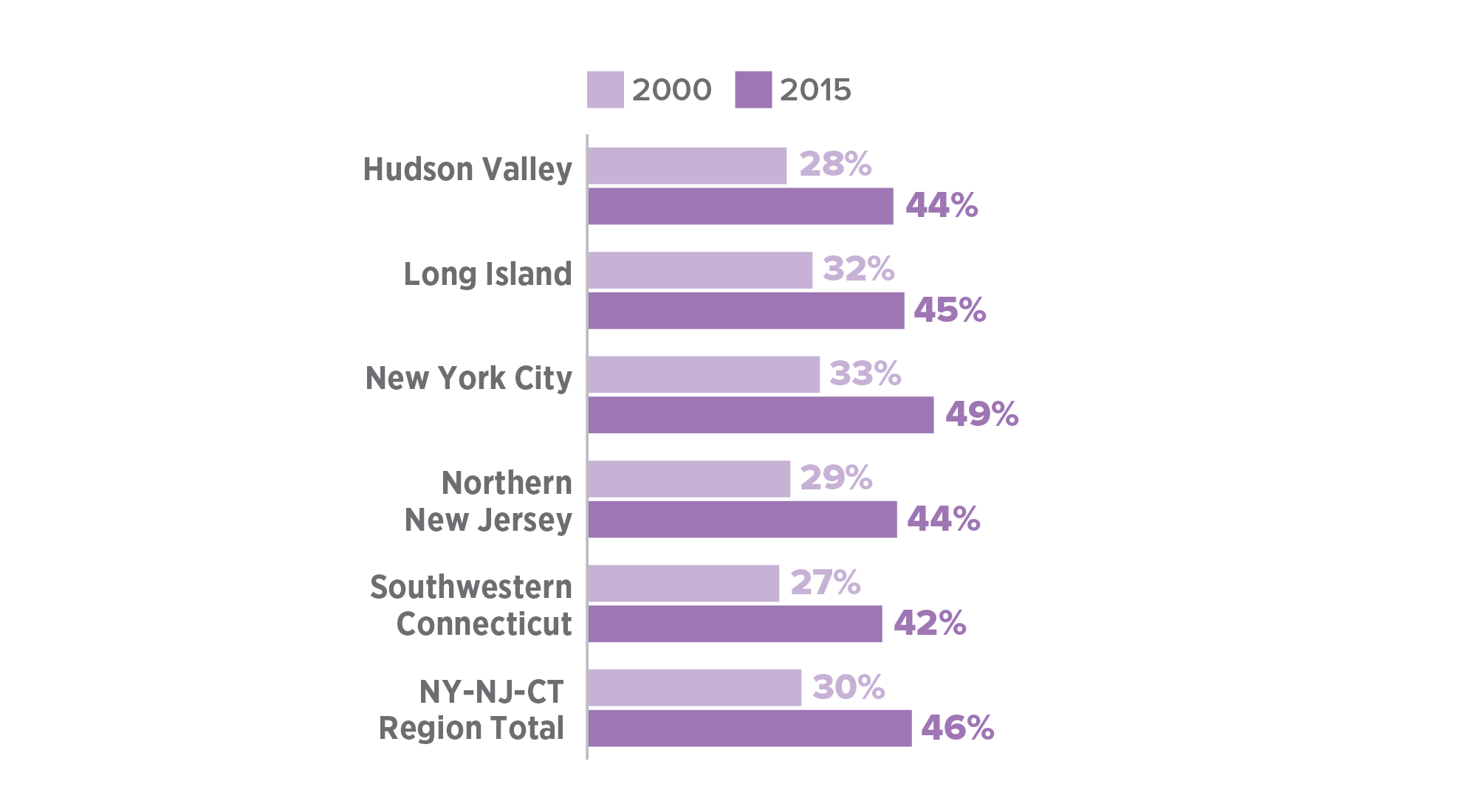

These dual crises of stagnant wages and rising costs are exacerbated by a legacy of discrimination in housing, transportation, education, and other policies that limit opportunities for low-income residents and people of color. Although the tri-state region is one of the most diverse in the country—nearly half of all residents are people of color, and a third are foreign-born—it is also one of the most segregated.

Growth patterns within the region have changed dramatically over the last generation. Many urban areas have been reinvigorated, but that transition has put new strains on city housing markets and suburban economies.

In the second half of the 20th century, suburbs grew quickly as middle-class and affluent city dwellers were able to take advantage of federal and local policies that promoted suburban home ownership. Cities were left behind, and struggled with growing unemployment, poverty, and crime. Over the last two decades, that trend has reversed, as people and jobs returned to New York and well-positioned cities such as Jersey City, White Plains, and Stamford.

For many towns, villages, and rural communities, this reversal has resulted in fewer local jobs, an aging population, and a smaller tax base. And many older, industrial cities are still struggling to grow their economies.

But for New York and other growing cities, the return of jobs and people has presented new challenges: rising real estate prices and rents, families displaced by unaffordable housing, and neighborhoods that longtime residents no longer recognize as their own. This growth has also put additional pressure on the region’s aging infrastructure, including subways and roads.

The failure to invest in improvements and build new infrastructure has led to disruptions and unreliable services, which are further strained by the impact of severe storms, heat waves, and catastrophic events like Superstorm Sandy and Hurricane Irene. Lives are senselessly lost, and the economic toll registers in the billions of dollars.

Metropolitan regions around the world are taking on these problems by investing in neighborhoods and business districts; building modern infrastructure that increases capacity, improves resilience, and boosts economic competitiveness; and adopting innovative solutions to protect coastal areas.

Yet in our region, government institutions fail to make the difficult decisions necessary to address the persistent problems of affordability, opportunity, and resilience.

We haven’t amended land-use and building regulations to facilitate the construction of more homes and encourage the development of communities that accommodate families of different incomes. We haven’t sufficiently reformed planning, management, or labor practices to reduce the high costs and slow pace of building new infrastructure. We haven’t modified tax structures to be more fair and promote a more productive and diversified economy. We haven’t built new public transportation to make sure people arrive at their jobs and schools faster. We haven’t done enough to update our technology infrastructure and reduce the digital divide. And we haven’t invested in the physical and natural systems that make our society and economy more resilient when disaster strikes.

Vision for the future

The Fourth Regional Plan is guided by four core values that serve as a foundation across issue areas.

Equity

In an equitable region, individuals of all races, incomes, ages, genders, and other social identities have equal opportunities to live full, healthy, and productive lives. The investments and policies proposed by RPA would reduce inequality and improve the lives of the region’s most vulnerable and disadvantaged residents.

Goal: By 2040, the tri-state region should sharply reduce poverty, end homelessness, close gaps in health and wealth that exist along racial, ethnic, and gender lines, and become one of the least segregated regions in the nation instead of one of the most segregated.

Health

Everyone deserves the opportunity to live the healthiest life possible, regardless of who they are or where they live. The Fourth Regional Plan provides a roadmap to address health inequities rooted in the built environment to create a healthier future for all.

Goal: By 2040, conditions should exist such that everyone is able to live longer and be far less likely to suffer from mental illness or chronic diseases such as asthma, diabetes, or heart disease, with low-income, Black and Hispanic residents seeing the greatest improvements.

Prosperity

In a prosperous region, the standard of living should rise for everyone. The actions in the Fourth Regional Plan will create the robust and broad-based economic growth needed to lift all incomes and support a healthier, more resilient region.

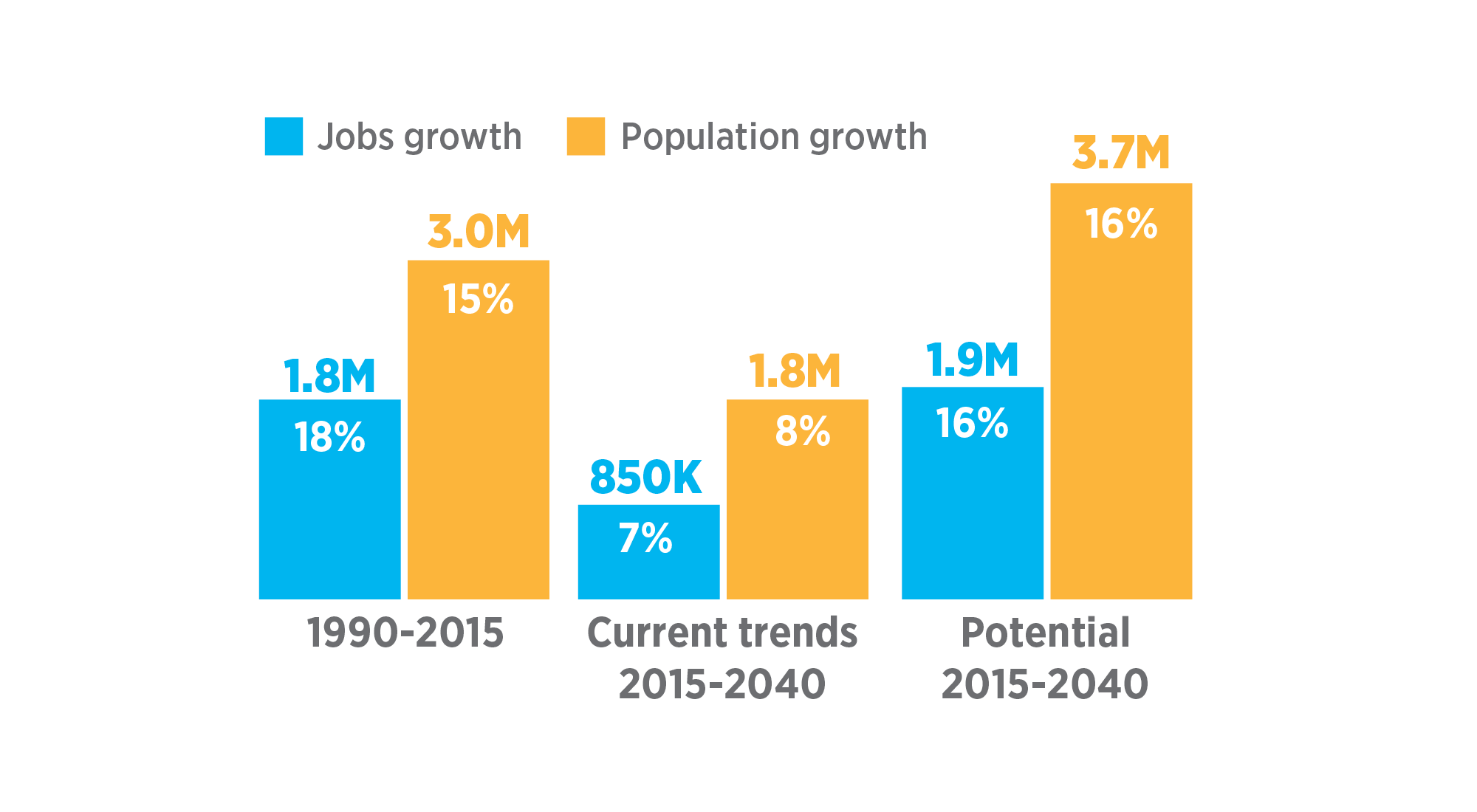

Goal: By 2040, the tri-state region should create two million jobs in accessible locations, substantially increase real incomes for all households, and achieve a major boost in jobs and incomes for residents in the region’s poorer cities and neighborhoods.

Sustainability

The region’s health and prosperity depend on a life-sustaining natural environment that will nurture both current and future generations. To flourish in the era of climate change, the fourth plan proposes a new relationship with nature that recognizes our built and natural environments as an integrated whole.

Goal: By 2040, the region should be nearing its goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 80 percent, eliminating the discharge of raw sewage into its rivers and harbor, and greatly improving its resilience to flooding and extreme heat caused by climate change.

The plan is organized into four action areas that represent major challenges and areas of opportunity.

Institutions

Our infrastructure is deteriorating, and it takes too long and costs too much to fix. Housing policies, local land-use practices, and tax structures are inefficient and reinforce inequality and segregation. Public institutions are slow to incorporate state-of-the-art technology to improve the quality of services. And truly addressing the growing threat of climate change requires investments far more ambitious and strategic than we have made so far. Solving these existential challenges will require public officials and citizens to reassess fundamental assumptions about public institutions.

Transportation

Transportation is the backbone of the region’s economy. It is also vital to the quality of life of everyone who lives and works here. But years of population and job growth and underinvestment in both maintenance and new construction have led to congestion, lack of reliability, and major disruptions on a regular basis. Some transportation improvements are relatively quick and inexpensive, such as redesigning our streets to accommodate walking, biking, and buses. But the region also needs to invest in new large-scale projects to modernize and extend the subways and regional rail networks, as well as upgrade airports and seaports. These investments will have far-reaching and positive effects on land use, settlement patterns, public health, goods movement, the economy, and the environment.

Climate change

Climate change is already transforming the region. Reducing the region’s greenhouse gas emissions is critical, but it won’t be enough. We must accelerate efforts to adapt to the impact of a changing climate.

Today, more than a million people and 650,000 jobs are at risk from flooding, along with critical infrastructure such as power plants, rail yards, and water-treatment facilities. By 2050, nearly two million people and one million jobs would be threatened. We must adapt our coastal communities and, in some cases, transition away from the most endangered areas. We will also need to invest in green infrastructure in our cities to mitigate the urban heat-island effect, reduce stormwater runoff and sewer overflows, and improve the health and well-being of residents.

Affordability

Over the last two decades the tri-state region has become more attractive to people and businesses—but it has also become more expensive. While household incomes have stagnated, housing costs have risen sharply, straining family budgets and resulting in increased displacement and homelessness. What’s more, the region’s history of racial and economic discrimination has kept many residents away from neighborhoods with quality schools and good jobs. Instead, many live in areas that are unsafe or environmentally hazardous. The region needs quality housing for all income levels in places that have good transit service. It must also invest in smaller cities and downtowns to boost economic opportunities throughout the region.

Key recommendations of the Fourth Regional Plan

The Fourth Regional Plan details 61 recommendations to make our region more equitable, healthy, sustainable, and prosperous. Here is an overview of the most urgent and potentially transformative ideas.

Reform regional transportation authorities and reduce the costs of building new transit projects

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority were created in the 1920s and the 1960s to address the challenges of their respective eras. The region has evolved since then, but the agencies haven’t. To fix our transportation system and expand capacity, we need to restructure the authorities that manage them.

RPA recommends reforming the governing and operating structures of both the MTA and the Port Authority to ensure they are more transparent, accountable, and efficient. Only then can the agencies regain the public’s trust and support for investing in costly new projects.

Specifically, RPA recommends the governor of New York establish a new Subway Reconstruction Public Benefit Corporation to overhaul and modernize the subway system within 15 years, thereby creating a transportation system suitable to meeting the needs of the largest, most dynamic metropolitan area in the nation.

RPA also recommends the Port Authority take immediate steps to depoliticize decision-making. Longer term, the Port Authority should create independent entities to manage the daily operations of its different assets (airports, ports, bus terminal, PATH, bridges, and tunnels). The central Port Authority body could then focus on its function as an infrastructure bank that finances large-scale projects.

Price greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions using California’s comprehensive approach

The region has already cut GHG emissions, but reaching the goal adopted by all three states and New York City—reducing emissions 80 percent by 2050—will require more dramatic action. RPA recommends strengthening and expanding the existing carbon pricing system, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, RGGI, to include emissions from the transportation, residential, commercial, and industrial sectors, as California has done. The three states could eventually join California and other jurisdictions to form a larger and more powerful cap-and-trade market.

The additional revenues that would be generated—potentially $3 billion per year in the three states—could be used to invest in creating an equitable, low-carbon economy and increasing our resilience to climate change.

Establish a Regional Coastal Commission and state adaptation trust funds

Climate change and rising sea levels do not stop at any border, yet resilience efforts so far have been managed at the municipal and state levels, with a complex and overlapping bureaucracy and scattered funding.

RPA recommends New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut create a Regional Coastal Commission that would take a long-range, multi-jurisdictional, and strategic approach to managing coastal adaptation. The states should simultaneously establish Adaptation Trust Funds to provide a dedicated revenue stream for resilience projects. Funding should be determined by the Coastal Commission using a clear set of standards and evaluation metrics that include both local and regional impacts on flooding, ecological conditions, the economy, fiscal conditions, as well as public health and neighborhood stability, particularly for the most vulnerable and those with fewest resources.

Increase civic engagement at the local level and make planning and development more inclusive, predictable, and efficient

Local governments are responsible for most of the decisions that shape the daily lives of residents. Yet few residents participate in community decision-making, and those who do are not representative of their communities in terms of race, age, and income level. As a result, local institutions make decisions that often reflect the values and needs of older, wealthier, and mostly white residents rather than the overall population.

In addition, public review processes for development projects are too complex and unpredictable, which increases costs and delays, or prevents too many good projects from being completed. All too often, when government agencies evaluate projects, they fail to adequately consider effects on health, affordability, the economy, and the environment.

RPA recommends local governments engage with the public more effectively by making better use of technology and data, adopting participatory budgeting, and ensuring residents have more influence in decision-making. The planning process should be reformed to engage residents earlier in the process, establish a fixed timeline for community input and government approvals, and incorporate health-impact assessments. These initiatives will lead to decisions that better reflect community needs and aspirations.

Levy charges and tolls to manage traffic and generate revenue

There is no logic to the way we manage our limited road capacity, from the congested streets of Midtown Manhattan to our interstate highways. Now, dozens of state, local, and regional agencies are responsible for these roads, and policies vary widely and seldom use market principles to improve service.

Adding tolls to all crossings into Manhattan south of 60th Street would reduce traffic congestion in the core of the region, make trips by car more reliable and goods delivery more efficient, and free up space for buses, bikes, and pedestrians. Tolls would also generate much-needed revenue for roads and transit.

In addition to this congestion charge for the core of the region, departments of transportation and highway authorities across the region should use tolls to reduce traffic on all highways, which would make driving times more reliable while also generating revenue. Highway and bridge tolls could, in the long term, be replaced with a fee on all vehicle-miles traveled, or with tolls that vary depending on time of day and levels of congestion. Every two cents charged per mile driven on the region’s highways would raise about $1 billion a year.

Modernize and expand New York City subways

After decades of underinvestment, the subway system is rapidly deteriorating at a time of record ridership.

RPA recommends the creation of a special public benefit corporation to be in charge of completely modernizing the subway system within 15 years (see recommendation above). Specific proposals include accelerating the adoption of modern signaling systems, and redesigning and renovating stations to reduce crowding, make the ambient environment healthier, and improve accessibility to people with disabilities.

To accomplish these large-scale improvements in a timely way, RPA recommends the MTA adopt policies with a greater tolerance for longer-term outages (as the MTA is already doing for the L train repairs), and evaluate replacing weeknight late-night subway service with robust bus service (when streets are traffic-free). Having longer windows for maintenance work would help keep the system in a state of good repair in the long term.

The MTA should also begin to expand the subway system into neighborhoods with the densities to support fixed-rail transit, particularly low-income areas where residents depend on public transportation. These strategic extensions would provide a better, more time- and cost-effective option for more residents, foster economic opportunities, and reduce traffic congestion. The fourth plan recommends building eight new lines and extensions in four boroughs.

Create a unified, integrated regional rail system and expand regional rail

Outside New York City, our region has three of the busiest commuter rail systems in the country and bus systems that serve millions of local, regional, and long-distance trips. Funding for these systems has not kept pace with growing ridership, and in some cases has been drastically cut. NJ Transit, Metro-North, and the Long Island Rail Road need to scale up operations to serve this increased demand. RPA recommends increasing funding to these entities, and reforming their governance structures to promote innovation and coordination.

RPA also envisions a series of new projects, phased in over the next few decades, to unify the commuter rail system and expand it into a seamless regional transit system. The resulting Trans-Regional Express (T-REX) would provide frequent, reliable service, directly connecting New Jersey, Long Island, the Mid-Hudson, and Connecticut, create new freight-rail corridors, and provide additional transit service to riders within New York City. T-REX would enable the transit system to comfortably serve an additional one million people by 2040, and support a growing regional economy.

Design streets for people and create more public space

RPA recommends cities and towns across the region rebalance their street space to prioritize walking, biking, transit, and goods deliveries over private cars. Managing street space more strategically will be particularly important as shared, on-demand, and, ultimately, driverless vehicles become more commonplace. Cities and towns should take a number of measures to ensure these vehicles improve mobility and don’t result in more congestion, including creating protected bus lanes, repurposing parking lanes for bus/bike lanes, rain gardens or wider sidewalks, and “geofencing” particular districts to prevent vehicle use at certain times of day.

Designing streets for people will make lower-cost transportation like biking, walking, or riding the bus safer and more pleasant, and encourage healthy physical activity. Prioritizing public transportation is particularly important for lower-income residents who disproportionately rely on buses.

RPA also recommends larger, more crowded cities such as New York expand access to public spaces in more creative ways. This could include reopening streets and underground passageways, and integrating some privately owned spaces, such as building lobbies, into the public realm.

Expand and redesign John F. Kennedy and Newark International airports

The region’s airports need more capacity to meet growing passenger and freight demand and to maintain economic competitiveness. RPA recommends phasing out Teterboro Airport, which will be permanently flooded by just one foot of sea-level rise. Improvements are already underway at LaGuardia Airport, which over the long term will need to expand capacity to handle larger aircraft.

JFK Airport should be expanded and modernized to include two additional runways, larger and more customer-friendly terminals, and significantly better transit access. Newark International Airport should be reconfigured, moving the main terminal closer to the train station on the Northeast rail corridor and freeing up more space to eventually construct a new runway. These improvements would allow the region’s airports to handle a projected 60 percent increase in passengers and reduce delays by 33 percent.

Strategically protect land to adapt to climate change and connect people with nature; establish a national park in the Meadowlands and a regional trail network

Even if we aggressively reduce our carbon emissions, climate change is here to stay. Our coastline will move inland, with up to six feet of sea-level rise possible by the beginning of the next century. There will be more frequent storms and days of extreme heat. To increase the region’s resilience to storms, floods, and rising temperatures, we must reconnect our communities to nature.

RPA proposes establishing a national park in the New Jersey Meadowlands, one of the Northeast’s largest remaining contiguous tracts of urban open space. The Meadowlands supports a wide array of wildlife and biodiversity, and has the potential to protect surrounding communities from storm surges. A Meadowlands National Park would protect this fragile ecosystem and also help educate the public about climate change adaptation.

RPA also calls for creating a 1,620-mile tri-state trail network, building on existing and planned trails and establishing new connections to create a comprehensive network linked with transit. Almost nine million residents would live within a half-mile of a trail—nearly 25 percent more than today.

Create a greener, smarter energy grid

Without significant new investment, the electrical grid will not be capable of handling increased demand due to population and job growth, the digital economy, and electric vehicles. Scaling up production of renewable energy and creating a cleaner, modern grid would also require better coordination among energy providers and regulators across the three states.

RPA recommends creating a Tri-State Energy Policy Task Force to enable a more reliable, flexible, cleaner, and greener network. This task force should develop a comprehensive plan to utilize emerging renewables such as wind, solar, and storage technology; integrate distributed generation; and make the grid smarter and more efficient. As cleaner fuels generate more power, existing electricity-supply facilities—including fast-ramping plants necessary for rapid changes—could be updated and used more effectively.

Preserve and create affordable housing in all communities

Affordability is key to giving everyone in the region the chance to succeed. RPA recommends several actions by all levels of government to protect and increase the supply of homes for households of all incomes, and create affordable housing in all communities. Many of these recommendations will facilitate the creation of new housing without additional funding. RPA also calls on cities and states to be more proactive in protecting vulnerable residents from displacement through policies that generate more permanently affordable housing and increase wealth in lower-income communities.

Municipalities should update zoning to facilitate more housing production, especially near transit. Some common-sense changes include allowing accessory dwellings, which could create 300,000 new units regionwide without any new construction. Others include ensuring all municipalities allow multifamily developments near transit stations, so residents can take advantage of technology-enabled vehicles that minimize the need for parking. Developing existing parking lots in this way would yield a quarter of a million new homes in walkable, mixed-income communities near transit.

These new homes can be accessible to all the region’s residents—existing as well as newcomers—by robust enforcement of fair housing protections and a region-wide inclusionary zoning policy, thereby creating diverse, mixed-income communities.

Create well-paying job opportunities throughout the region

Increasing incomes is essential to solving the affordability challenge, and that requires a diverse economy with good jobs in accessible locations for people with a variety of skills and education levels.

Manhattan’s central business district (CBD) could become a more powerful engine for the region’s economy by expanding to the south, east, and west; preserving Midtown’s older, less-expensive office space to accommodate different types of businesses; and creating more mixed-residential and job districts near the CBD.

Cities such as Bridgeport, Paterson, and Poughkeepsie could become regional centers for new jobs in a range of industries, by building on existing urban assets and revitalizing downtowns with financial and policy support from state government.

RPA also recommends municipalities partner with local anchor institutions such as hospitals and universities to develop career pathways for training and hiring local residents. These institutions, which have a great procurement power, can also create and support local supply chains that benefit the surrounding neighborhoods, the city, and the region as whole.

In addition, RPA urges municipalities to preserve existing industrial space for that purpose, while also creating facilities for smaller high-tech manufacturers that will drive industrial job creation in the coming decades.

The fourth plan in context

About Regional Plan Association

Since its inception nearly a century ago, RPA has conducted groundbreaking research on issues of land use, transportation, the environment, economic development, and opportunity. It has also led advocacy campaigns to foster a thriving, diverse, and environmentally sustainable region, helping local communities address their most pressing challenges.

RPA staff includes policy experts, urban planners, analysts, writers, and advocates. RPA collaborates with partners across sectors to find the best ideas to meet the challenges facing our region today and in the future.

RPA’s work is informed by these partnerships as well as by our Board of Directors and our New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut Committees.

How was the Fourth Regional Plan developed?

RPA began work on the Fourth Regional Plan by speaking with residents and experts and aggregating data. RPA’s report “Fragile Success,” published in 2014, assessed and documented the region’s challenges: affordability, climate change, infrastructure, and governance.

Utilizing detailed land-use data and intricate econometric models, RPA documented the region’s built form, quantified population and employment trends, and extrapolated future growth scenarios. The 2016 report “Charting a New Course” compared these scenarios and presented an optimal growth pattern that would achieve several benchmarks of success. This aspirational scenario guided recommendations developed for the Fourth Regional Plan.

Throughout the process, RPA staff worked with hundreds of experts in housing, transportation, land use, and environmental issues. And we received regular feedback over the years at nearly 200 meetings and forums, where we held discussions with some 4,000 people.

RPA staff also engaged in deep, multi-year collaborations with community organizations including Make the Road New York, Make the Road Connecticut, Community Voices Heard, Housing and Community Development Network of New Jersey, Partnership for Strong Communities, Right to the City Alliance, and others. These organizations, which represent more than 50,000 low-income residents and people of color, helped RPA staff hear a wide range of perspectives on affordability, jobs, transportation, and environmental justice. This effort enabled us to stay connected at the grassroots level—no easy task in a region with 23 million residents.

RPA’s past plans have shaped the tri-state region

Since the 1920s, RPA has developed groundbreaking long-range plans to guide the growth of the New York-New Jersey-Connecticut metropolitan area.

These efforts have shaped and improved the region’s economic health, environmental sustainability, and quality of life. Ideas and recommendations put forth in these plans have led to the establishment of some of the tri-state region’s most significant infrastructure, open space, and economic development projects, including new bridges and roadways, improvements to our transit network, the preservation of vital open space, and the renewed emphasis on creating sustainable communities centered around jobs and transit.

Regional Plan of New York and Its Environs, 1929

RPA’s first plan in 1929 provided the blueprint for the transportation and open space networks we take for granted today. Major recommendations that shape the region today include:

- A more connected region with better railroads, highways, and parks. The goal was to provide access to more of the region and give options for living beyond the overcrowded core. The fundamental concept of metropolitan development driven by transit and limited-access highways, pioneered in the first plan, created a precedent for every modern 20th century metropolis.

- The proposed network of highways led to the relocation of the planned George Washington Bridge from 57th to 178th Street. RPA understood the bridge would primarily be used for traveling through the region, and should therefore avoid the congestion of Midtown. The construction of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge in the early 1960s effectively completed the regional highway system proposed in RPA’s first plan.

- The first plan’s call for preserving large swaths of natural areas, as well as the identification of the most critical areas to be preserved, persuaded several public agencies to purchase and preserve land. Acquisitions in Nassau, Suffolk, Putnam, and Dutchess counties, and in Flushing Meadows, Orchard Beach Park, and the Palisades, doubled the region’s park space.

- RPA helped local governments establish planning boards, including New York City’s City Planning Commission, to advise local elected officials on development decisions. From 1929 to 1939, the number of planning boards in the region increased from 61 to 204. Today, they are an essential component of local land-use and budget planning in the region.

Second Regional Plan, 1968

The Second Regional Plan envisioned a regional network of economic centers connected by robust and federally funded mass transit. At a time when middle-class and wealthier Americans were fleeing cities for residential suburbs, RPA called for concentrating areas of economic development and building the transit network for these urban centers to thrive. Major recommendations of the second plan that shape the region today include:

- The federal Urban Mass Transportation Act adopted RPA’s principle of federal support for capital costs for urban mass transit. By ensuring adequate funding, the region’s transit agencies were able to plan for the long term. RPA supported the formation of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which brought together the subway, bus, commuter rail, and many bridge-and-tunnel toll facilities under one roof.

- The second plan identified the potential for revitalizing the Lower Hudson River area with better infrastructure, housing, and public parks. Its vision for Manhattan, Hoboken, and Jersey City has largely become reality, with better transit, an attractive waterfront, and mixed-use development.

- RPA called for the revival of regional centers in Jamaica, Queens, Downtown Brooklyn, Newark, NJ, and Stamford, CT.

- RPA introduced the concept that the supply of undeveloped natural spaces was limited and called for an aggressive program to acquire, protect, and permanently preserve natural landscapes for future generations. RPA led the effort to create Gateway National Recreation Center, which in 1972 became the first major federal recreation area in an urban setting.

Third Regional Plan, 1996

A cornerstone of RPA’s Third Regional Plan was the recognition that the region’s continued prosperity and global standing were no longer guaranteed. A severe economic downturn hit New York in the early 1990s, and by 1996 it was still uncertain whether the economy could fully recover. The Third Regional Plan called for renewed economic development in New York City, and investing in schools, rail systems, community design, and natural resources to accelerate economic recovery. Major recommendations of the third plan built or in progress include:

- The redevelopment of the Far West Side to expand the Midtown business district helped shape RPA’s alternative development scenario for the Hudson Yards when city leaders proposed building a football stadium on the site. The plan ultimately adopted by the city and developers closely resembled RPA’s proposal.

- The third plan proposed a new rail system to connect existing commuter rail lines and optimize the transit system as a whole, including a Second Avenue Subway (the first phase of which is now built) and a connection for Long Island Rail Road into Grand Central, known as East Side Access (now under construction).

- The third plan set in motion steps that led to the permanent conservation of several region-shaping open spaces, including Governors Island, the New Jersey Highlands, and the Central Pine Barrens.

From plan to implementation

The Fourth Regional Plan looks ahead to the next generation. A long-range plan allows RPA to set our sights high and not be constrained by current political dynamics. But we know a generation is too long to wait for families facing the pressures of rising rents and stagnating wages, for workers facing long and unreliable commutes, and for coastal communities on the front lines of more frequent and extreme flooding.

And so the fourth plan is the long-term strategy that also informs our short-term advocacy efforts.

If we succeed in implementing the vision and recommendations outlined in the Fourth Regional Plan, the region will be more equitable, healthy, sustainable, and prosperous. The plan provides a model for growth that creates a larger tax base to finance new infrastructure, an expanded transit network, more green infrastructure to protect us from the impacts of climate change, as well as sufficient affordable housing and other necessities that together create a virtuous cycle.

Regional Plan Association will build on the partnerships it has created through the development process for this plan to ensure its recommendations are debated, refined, and ultimately implemented. The continued success of the region and all of its residents depends on it.

Paying for it

Addressing these challenges would require significant investment.

The plan recommends ways to reform the way new rail infrastructure projects are designed and built to reduce their cost. The plan also suggests redirecting funding from low-impact programs to more effective ones. With these measures, we will be able to grow the economy, increase the tax base, and generate new revenue.

But even with significant budget savings and a growing economy, more funding would still be needed. RPA proposes new funding streams that would more fairly distribute the burden of taxes, fees, and tolls, while promoting strategic policy goals. These include sustainable patterns of development, more equitable distribution of wealth and income, energy efficiency, and climate resilience.

New or underutilized funding streams identified in this plan include:

- Pricing greenhouse gas emissions to fund climate adaptation and mitigation measures, transit, and investments in environmentally burdened neighborhoods

- Highway tolling and congestion pricing to fund investment in our highways, bridges, and transit

- Value capture from real estate to fund new transit stations or line extensions, as well as more affordable housing near transit

- Insurance surcharges on property to fund coastal climate adaptation

- Reforming housing subsidies to fund more low-income housing

What the future could look like

To demonstrate how the policies and projects recommended in this plan could shape the places where we live and work, RPA described potential futures for nine “flagship” places that represent unique communities, built environments, and natural landscapes. In each flagship, we highlight the challenges and opportunities found elsewhere in the region. These narratives are intended to be illustrative and inspirational, rather than prescriptive.

- Jamaica: A business hub tied to neighboring communities and JFK Airport

- Bridgeport: A green and healthy city on the Northeast Corridor

- Meadowlands: A national park for the region

- The Far West Side: A new anchor for the region’s core

- Triboro Line: A new transit link for the boroughs

- Central Nassau: New transit for a diverse suburb

- Newburgh: A model of equitable and sustainable development in the Hudson Valley

- Paterson: Connecting a former factory town to the region’s economy

- Inner Sound: Industry, nature, and neighborhoods in harmony