A majority of the region’s waters, despite significant improvements in recent decades, are still so polluted they contribute to health risks and are unfit for swimming, fishing, or supporting a biodiverse environment. The main recurrent sources of pollution, stormwater runoff and the discharge of combined stormwater and untreated sewage, will only get worse as climate change brings more frequent and intense storms. The federal government, states, and municipalities should work together to eliminate all combined sewer overflow by 2040. This will require incorporating green infrastructure strategies into building and zoning codes, and strengthening clean-water standards. We can accelerate this process by establishing neighborhood green districts that implement pilot projects, and by imposing a stormwater utility fee to fund and advance new infrastructure initiatives.

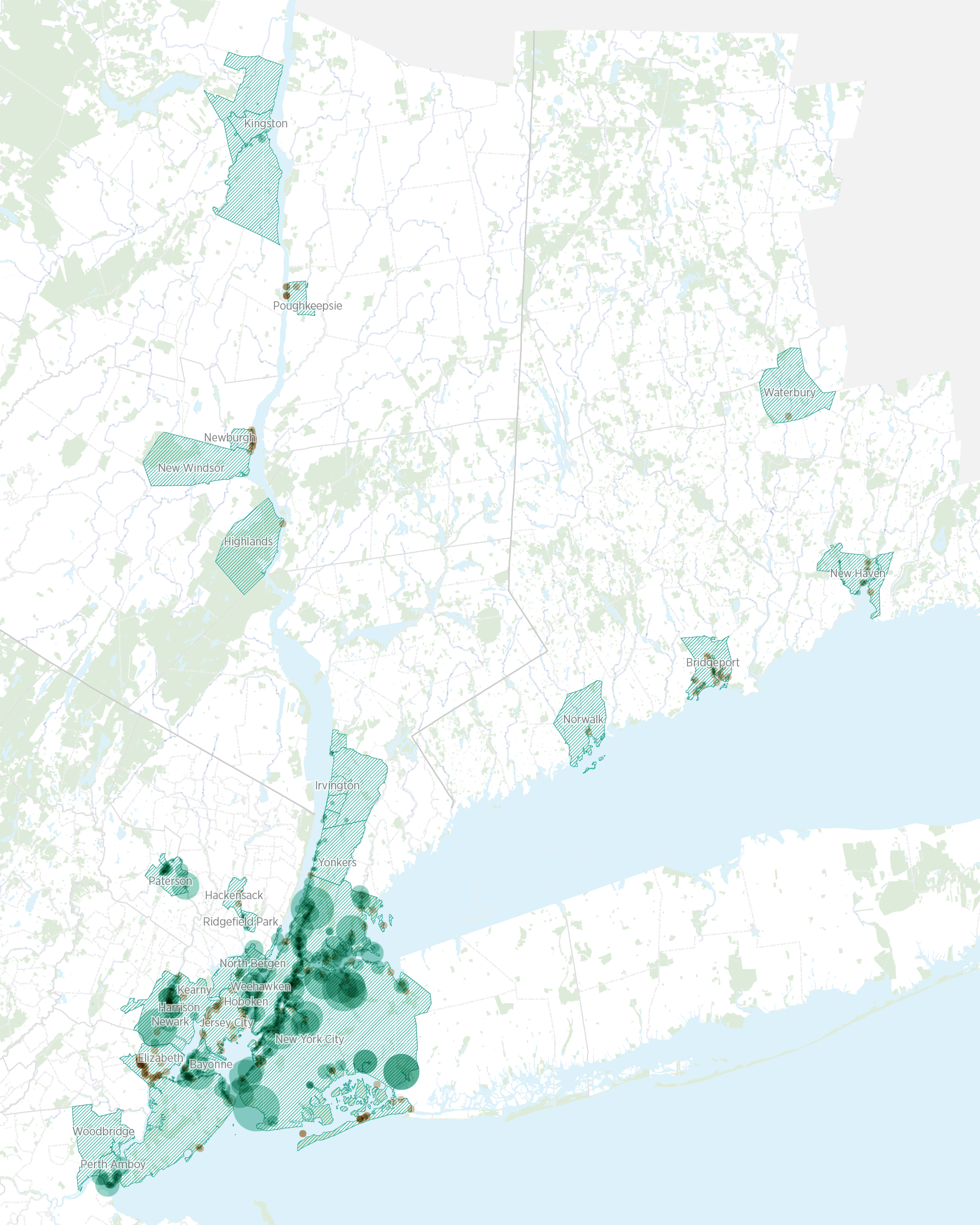

Many of the region’s sewer systems were built to collect stormwater together with domestic sewage and industrial wastewater. Unfortunately, in times of heavy rain, these systems overflow. In 39 municipalities across the tri-state region, there are 702 combined sewer overflow outfalls—places where untreated human and industrial waste, plus contaminants and debris, gets discharged directly into our rivers and ocean when there are periods of heavy rain.

Each year, more than 27 billion gallons of untreated wastewater and polluted stormwater discharge from 460 combined sewer overflow (CSO) outfalls into New York Harbor alone, with another nearly 300 CSOs in waterways throughout the region. These outflows present significant ecological and public health issues, as they generate algal blooms, reduce water quality and biodiversity, increase shellfish-bed and beach closures, and create the potential for waterborne-disease outbreaks. More sewage and pollutants will spill into these waterways as climate change brings intensified storms, threatening wetlands, oyster beds, and other natural systems that protect against flooding.

Communities that discharge raw sewage into waterways are required to have a plan to separate older-style combined sewer systems, store excess sanitary waste and stormwater until it can be treated, or otherwise control the discharges. Municipalities that are prepared for the future by scaling efforts to eliminate the discharge of polluted stormwater and untreated sewage into our waterways by 2040 will be better positioned to attract residents, businesses, and tourists with access to clean water.

New York City has adopted an approach that combines “green” and “grey” infrastructure improvements to reduce CSOs, investing $1.5 billion in public funds in green stormwater runoff mitigation strategies by 2030, and an additional $1.6 billion in grey infrastructure, including treatment-plant upgrades and the construction of large retention tanks to hold overflows until the polluted water can be treated. These investments will help the city reduce CSO discharges by approximately eight billion gallons per year.

Communities outside New York City in the Hudson Valley, northern New Jersey, and coastal Connecticut have fewer concentrations of CSOs, but the pollution and harm they cause are still significant, at 6.3 billion gallons per year. Like New York City, these areas are implementing plans to reduce flow through green and grey infrastructure investments.

Traditionally, municipalities have eliminated CSOs through costly sewer projects that separate the combined, single-pipe system into different sewers for sanitary and stormwater flows. While this may be an effective strategy, it would be cost-prohibitive and logistically challenging to complete throughout the region, particularly in the most densely developed cities.

To achieve zero CSO outfalls by 2040, municipalities will need to put a greater emphasis on a green-infrastructure-centered approach that uses nature-based features like parks, greenways, bioswales and rain gardens to soak up stormwater before it reaches the sewer. States should set strong water-quality standards that exceed federal minimums and encourage municipalities to deploy these green infrastructure strategies. Municipalities will need to invest in these systems using new financing tools, and plan at the watershed level.

Grey infrastructure is considerably more costly and has fewer co-benefits, but can remove greater quantities in a single project, and works best in places like Manhattan where bedrock lies below the surface and doesn’t allow for water infiltration.

Incorporating green roofs, rain gardens, permeable pavement, and water-retentive cisterns into new and renovated large-scale developments can reduce the load on a community’s stormwater management system. State planning and environmental protection agencies should require a higher standard of green infrastructure in all local building and zoning codes. In addition to reducing stormwater overflows, the cooling effect of green infrastructure has the benefit of mitigating the effects of urban heat island. Standards and practices should be updated as measurement and monitoring programs of green infrastructure installations determine the best applications for different conditions.

Uncovering streams that were buried or otherwise covered in pavement—known as daylighting—can also reduce the load on the stormwater system and alleviate the risk of flash flooding. Although daylighting streams can be complex and expensive, it could mitigate flooding risk, improve habitat, and provide aesthetically pleasing natural landscapes in urban communities that could boost surrounding property values. Recent projects in Yonkers, NY, and Stamford, CT, demonstrate the high return on investment of restoring buried or culverted streams.

States should develop evaluation metrics to identify the best daylighting opportunities, informed by historic ecologies, maintenance operations, and stewardship opportunities, as well as additional co-benefits such as recreational opportunities, potential community spaces, and the ability to measure success post-implementation. Such a cost-benefit analysis would provide a roadmap for future daylighting projects.

Stormwater utility fees provide both a dedicated revenue stream for stormwater management programs and a way to incentivize property owners to adopt best practices in green infrastructure and low-impact development. Water authorities should institute stormwater fee systems that charge property owners based on the area of impervious cover and how much stormwater flows off of the property. The revenue could be used to upgrade and maintain stormwater management systems and fund stream-restoration projects. Cities across our region could structure their utility-fee systems in ways that best suit their built environment, and establish different rates based on property types.

Green districts are a way to focus on green infrastructure projects in a distinct geographic area in order to see quick returns on investment. Although green districts are not appropriate in every context, they can help catalyze change. These projects are typically easier to implement when states and municipalities agree on the process for designating green districts, and what kind and how much funding they’ll each ultimately receive.

Some green districts are quite large, such as a network of interconnected parks, while others are no bigger than a neighborhood. For example, Philadelphia has had success implementing green infrastructure projects in small, concentrated clusters that gradually radiate out as they increase in size and area over time.

Communities seeking to transition some of their auto-dependent landscapes into complete neighborhoods should designate them as green districts in order to focus attention and investment where it could have the most impact.

Eliminating the occurrence of CSOs and capturing more stormwater would help end the continuing pollution of the region’s waterways, particularly from heavy stormwater runoff. It would also increase biodiversity and healthy habitats, and allow for more water-based activities such as swimming and fishing. More of the region’s waterways would become healthier and more attractive for communities, attract visitors, and improve the well-being of residents.

Eliminating all 702 CSOs across the region would require significant investments in a variety of projects, including green and grey infrastructure. Regional cost estimates are difficult to quantify given the differences in approaches, but New York City has estimated the cost of green infrastructure to be about $1 to $2/gallon of CSO avoided. Grey infrastructure is considerably more costly and has fewer co-benefits, but can remove greater quantities in a single project. It is likely the final price tag will be at least $10 billion. Achieving this goal by 2040 would require a combination of state and local funding. State funding for watershed wide projects and incentives could leverage municipal green infrastructure and daylighting projects. Stormwater utility fees based on the amount of impervious surfaces could substantially fund local shares.

1. Riverkeeper, “Combined Sewage Overflows (CSOs),” 20010