Whether to allow townhouses, apartments, and shops; under what conditions landlords are able to evict tenants; how to design and program public spaces; how to spend property tax revenue; and how much to invest in local schools—these are all decisions made by locally elected officials. By shaping the physical and fiscal realities of our communities, local elected officials affect how residents experience their communities every day.

But despite the outsized impact of local government, the share of people who participate in the regular workings of local democracy is extremely low. Even in high-profile mayoral elections, consistently fewer than one in three adult residents vote, and far fewer attend hearings or serve on local bodies like the zoning boards or school boards.

The main factor driving this poor participation is the lack of a direct “reward” for participating in local government. Many people do not know what local government does or how they can affect decisions. As consumers of goods and online social networks, we are consistently given information and feedback. But as citizens, the information we receive from government can be opaque, engagement is infrequent, and there is little expectation that government will be responsive.

In some communities, there is direct exclusion from government. Across the region, 2.6 million people cannot vote in local elections because they are not U.S. citizens and tens of thousands cannot vote because they are on parole or on probation. In Port Chester, NY; Union City, NJ; Hempstead, NY; and a dozen other municipalities, more than a third of all adults are not eligible to vote. Most of these residents pay taxes, send their children to public schools, participate in the civic life of their communities, and are knowledgeable about the challenges facing their neighborhoods, yet they are barred from participating. This represents a tremendous loss to the community because these residents are typically low income and of color, and their needs can be very different than their neighbors’.

This lack of participation has very real impacts on land use, local budgeting, and school policy. Decisions about these issues reinforce the region’s deepening inequality, limit economic opportunity for working families, stifle the sense of civic belonging, and lower the quality of life for many.

Local government leaders should use more of the tools at their disposal to engage with their constituents

Improving civic participation and trust will require reconnecting residents with their government and demonstrating that participation in local democratic efforts yields results.

Expand participatory budgeting

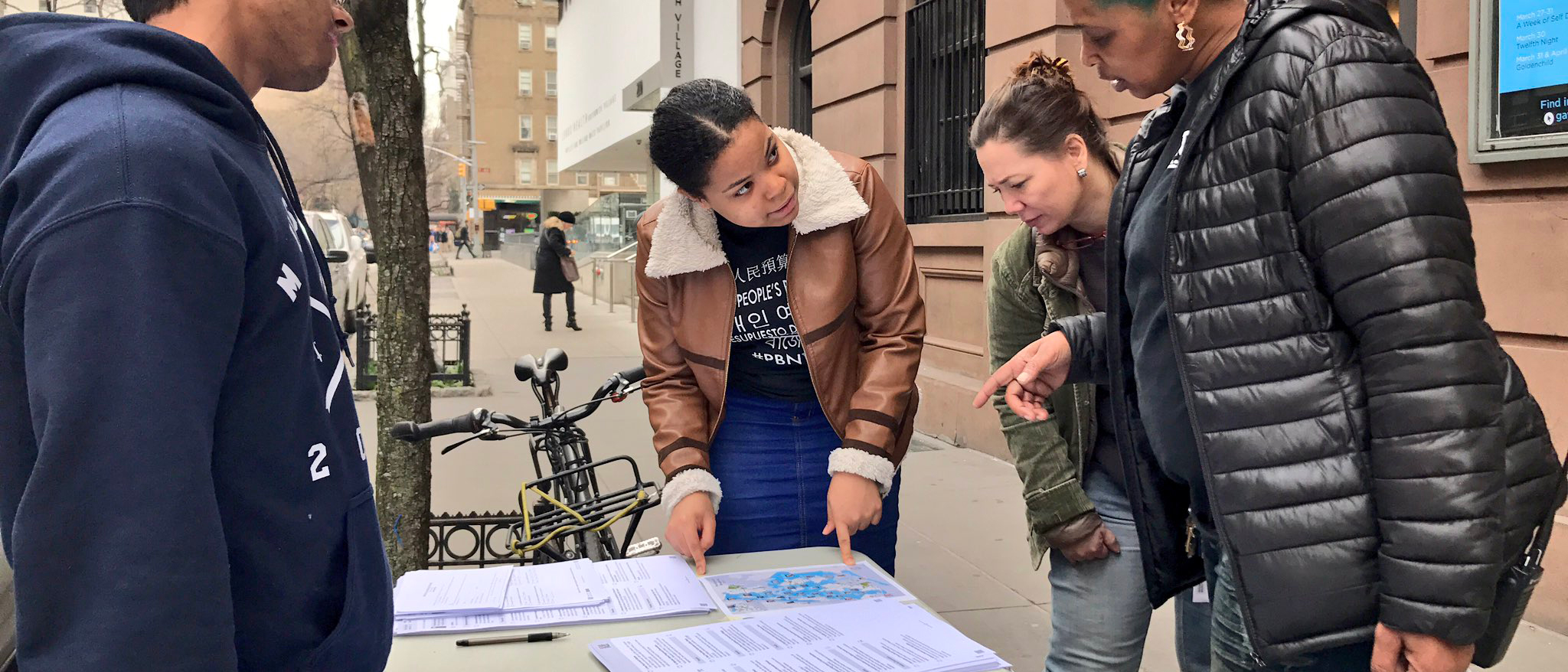

Participatory budgeting is a process that allows community members to decide how to spend a portion of a public budget to fund improvements to schools, parks, libraries, public housing, or other public projects. By making budget decisions clear and accessible, the participatory budgeting process motivates a wide range of residents to participate in local government decisions—even those who have not been involved before.

Participatory budgeting is not new to the region, but we have a long way to go until it reaches all residents. New York City leads the country in this regard, with more than 30 city council members allocating nearly $40 million for participatory budgeting. Participatory budgeting is being considered by residents and elected officials in Hempstead, NY; Stamford, CT; Bridgeport, CT; New Haven, CT; and statewide in New Jersey. CUNY-system colleges and even an elementary school have done participatory budgeting with students. Other cities and towns in the region should follow this lead and set aside a share of their municipal budget for allocation by local residents.

Use participatory planning to design healthier communities

A lot has been learned in the last ten years about how to create better streets through design, but more of these “placemaking” projects must be built. Communities can dramatically improve quality of life and public health outcomes by connecting community destinations, and creating a sense of place around them. Including all residents in the planning process, particularly those from more vulnerable populations, will help identify the projects of most value to the community. Examples include safe routes to health in Seattle, safe routes to school programs and walking buses, designing playgrounds in streets, using joint use agreements to create more open spaces, and creating a free public water supply and critical facilities in times of emergency such as cooling centers. These are all low-cost, high-impact ways to show that local public institutions are responsive to community needs.

Reform the development approvals process

Some of the most significant decisions made by local governments concern real estate development. Local governments must do more to inform the public of what projects are being considered, educate them about the broader dynamics at play, solicit their input, and keep them informed about construction updates. Among the recommendations for how to make these processes more inclusive are requiring municipal and community plans so projects reflect resident priorities, specifying timelines for community input, and working to diversify planning boards and commissions to better reflect the diversity of the communities they serve.

Make it easier and more rewarding to register and vote

Voting should be a convenient and rewarding experience. All states need to pass measures to simplify voter registration, promote early voting and voting by mail, and extend open hours at polling stations. Local elections should be scheduled to coincide with state and federal elections and communities should find more ways to reinforce the positive aspects of participating in democracy. Nobody should experience difficulty exercising their right to vote.

Give long-term residents a greater voice in local affairs

Many important decisions are made at the local level, including land use, investments in local amenities, and school budgets. In making these decisions, local government leaders better reflect the aspirations and needs of the community when they consider themselves to be accountable to all the people living in their jurisdiction. Residents, including long-term, non-citizen residents, who are invested in their community—who pay taxes, raise their families and send their children to public schools—should be able to have a say in local decisions that affect their lives. There are a range of strategies that can accomplish this goals, including publishing official documents in multiple languages, and holding hearings with translation services available. At the end of the spectrum, a few municipalities in the United States even allow non-citizen voting in limited circumstances. In San Francisco, for example, noncitizens who have children in the city’s school district can now vote in local school board elections. Local governments should adopt appropriate stategies to expand participation to all residents who will be affected by their decisions.

Allow those who have served their time to vote

In New York, formerly incarcerated persons must complete parole before they can vote. In New Jersey and Connecticut, the law is even stricter, requiring completion of both parole and probation. Our three states should follow the sixteen states across the country that allow those who have served their time to be reinstated as eligible voters. We all have a vital stake in reintegrating formerly incarcerated persons back into their communities. Allowing them to exercise their right to vote is an important step in that direction.

Government must assume a more active role in efforts to widen citizen participation in decision-making, and encourage elected officials to be more responsive and in touch with the communities they represent. Changing the voting laws to permit long-term residents and those formerly incarcerated to vote will ease disenfranchisement and allow many residents who have been shut out of the process to participate. Opening the budgetary process and making the decision-making more transparent will provide residents with a better idea of what government does and how it can respond to meet their needs. Over time, all of these reforms will greatly increase civic engagement and give residents a more prominent voice in the future of their own communities.

Paying for it

Overall, efforts to increase local participation in government—such as revising voting regulations, including residents in development decisions, and adopting participatory budgeting—would involve minimal costs.

Increasing the technological capacity of local government would take more resources over the long term. State governments should make available both financial incentives and training to local governments who wish to be more innovative in their engagement with constituents.

1. Seattle Neighborhood Greenways, “Safe Routes to Health,” 2014

2. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps, “Walking School Buses,” 2015

3. Child In The City Foundation, “Incorporating play into pedestrian walkways,” 2016

4. ChangeLab Solutions, “Fair Play: Advancing Health Equity through Shared Use,” 2015

5. American Planning Association, “Quenching Community Thirst: Planning for More Access to Drinking Water in Public Places,” 2013