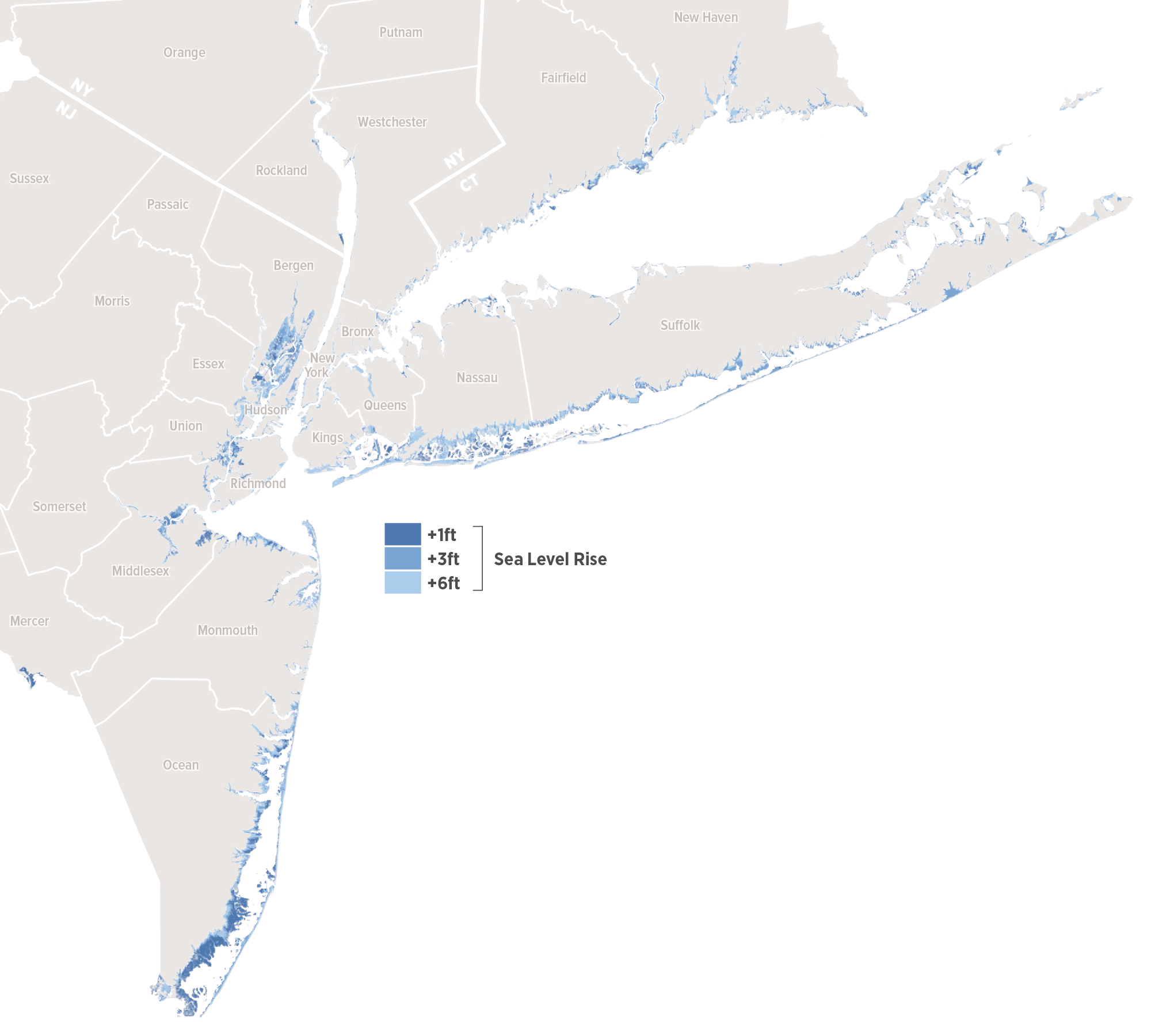

Superstorm Sandy galvanized the region to plan for coastal storm surges. A variety of adaptation plans and projects are underway, but few grapple with the difficult reality of sea-level rise and the permanent inundation it will bring to the lowest-lying areas. Communities that have settled on barrier beaches, back bays, and river floodplains are at particular risk, and within a few decades will need to be relocated. A small number of communities in New Jersey and on Staten Island and the south shore of Long Island have already begun to encourage residents to sell their property and move away. Many more communities need to plan for this transition—in the New Jersey Meadowlands, Long Island’s south shore, and the iconic Jersey Shore—and will need technical assistance to do it right. A further challenge is programs to buy out homeowners: while effective in the early stages of transition, buy-out programs will not be financially sustainable as currently conceived when entire communities need to be relocated.

Gradually move housing, commerce, and infrastructure away from low-density, flood-prone areas to higher ground

In the short term, an increasing number of municipalities would acknowledge the areas at greatest risk of flooding and destruction, and future development there would cease. Over time, building codes and zoning regulations would be updated, discouraging growth in the flood zone and encouraging resilient growth on lower-risk land as municipalities develop phased adaptation plans. Enhanced buyout programs and reliable adaptation funding would allow communities to make the transition, and much of the waterfront edge would be returned to nature to serve as a natural buffer from floods.

Benchmarks of success would include a robust network of municipalities sharing challenges, best practices, and long-term visions across a regional network by 2020. Development moratoriums in high-risk zones of lower-density waterfront municipalities would also be established by then.

By 2030, all coastal municipalities would have enacted building-code and zoning regulation changes that permanently ended risky development in flood zones, and would be in the process of implementing their phased, long-term adaptation plans. Improved and well-funded buyout programs would have returned to nature all unprotected areas subject to permanent flooding from one foot of sea-level rise by 2040, and three feet of sea-level rise by 2075.

Paying for it

Adapting our municipalities for long-term and permanent flooding will require significant public investment, and could ultimately result in lost tax revenue from lucrative waterfront properties. National flood insurance rates will begin to rise over the coming years, perhaps making affordability along the coast even more difficult and buyouts a more attractive option. All adaptation tools—from walls and pumps to buyouts—will require a large and stable source of funding.

In the long run, some costs could be offset by a reduced need for municipal services (evacuation, closed roadways, repairs to infrastructure) and personal expenditures (flooding repairs, mold, loss of workdays, health issues). Lost tax revenues can be restored by developing lower-risk areas, if the community has such land available. The high cost of adapting and retreating from the waterfront underscores the importance of developing Adaptation Trust Funds.

1. RPA, “Under Water: How Sea Level Rise Threatens the Tri-State Region,” 2017

2. RPA, “Buy-In for Buyouts,” 2016