The region’s three commuter railroads—Long Island Rail Road, Metro-North Railroad and New Jersey Transit—are an amalgamation of rail lines built largely by private railroads more than 100 years ago. This aging system was designed to get people in and out of Manhattan when the metropolitan area was less than half the size it is today. It poorly serves job centers outside of Manhattan, leaves many places without any rail service at all, isn’t configured to serve today’s 24-hour, multi-directional travel patterns, and is straining to serve the number of riders it has today, much less tomorrow. More specifically:

- Many assets—from stations and signals to tracks and interlockings—are well past their useful life or don’t meet modern standards.

- All service ends in Manhattan, preventing trains from traveling through from one part of the region to the other, and reducing the capacity of the system overall.

- While ridership is growing the fastest outside of morning and afternoon rush hours, service continues to be much worse on most lines at those times than during their peak.

- Reverse service into many job centers with strong growth potential, such as Bridgeport or Hicksville, is poor—and limits the ability of those downtowns to grow into major economic hubs. Some large downtowns such as Paterson have no direct service at all.

- Many residential areas with densities to support commuter rail service don’t have it, including much of Bergen, Passaic, and Monmouth counties.

- Service is too infrequent or too expensive for many residents in the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, Hudson, and Essex counties.

- Many parts of the system are already operating well past their capacity, including the rail tunnels under the Hudson River used by all New Jersey Transit trains, Penn Station, and Metro-North’s New Haven line. Over the next 25 years, the number of people commuting from the suburbs into Manhattan could grow by as much as 34 percent, much more than the current system can handle.

- Fragmented control of the system among the different railroads makes it difficult to plan for upgrades and repairs or provide holistic, integrated service.

Many of New York City’s peers, such as Paris and London, have transformed their traditional commuter rail systems to run more like urban metro systems. With more frequent and convenient service to, in, and through the city centers, those systems have increased businesses’ access to a large and varied labor pool. They have also given residents access to more jobs and more housing choices. New York’s disjointed system is holding us back from becoming a truly integrated and economically powerful region.

The region must modernize, integrate, and expand its commuter rail network to keep up with a growing region, as well as changing technology and service demands. Unifying the network into a Trans-Regional Express service that vastly improves mobility throughout the region will require major infrastructure upgrades to integrate its different components and then expand it. Some actions, like building additional tunnels under the Hudson and creating a more functional Penn Station, address urgent needs and should begin immediately. Others will take a decade or more to be planned and approved. But all improvements should be designed to allow future projects to rationalize and synchronize service as they expand capacity.

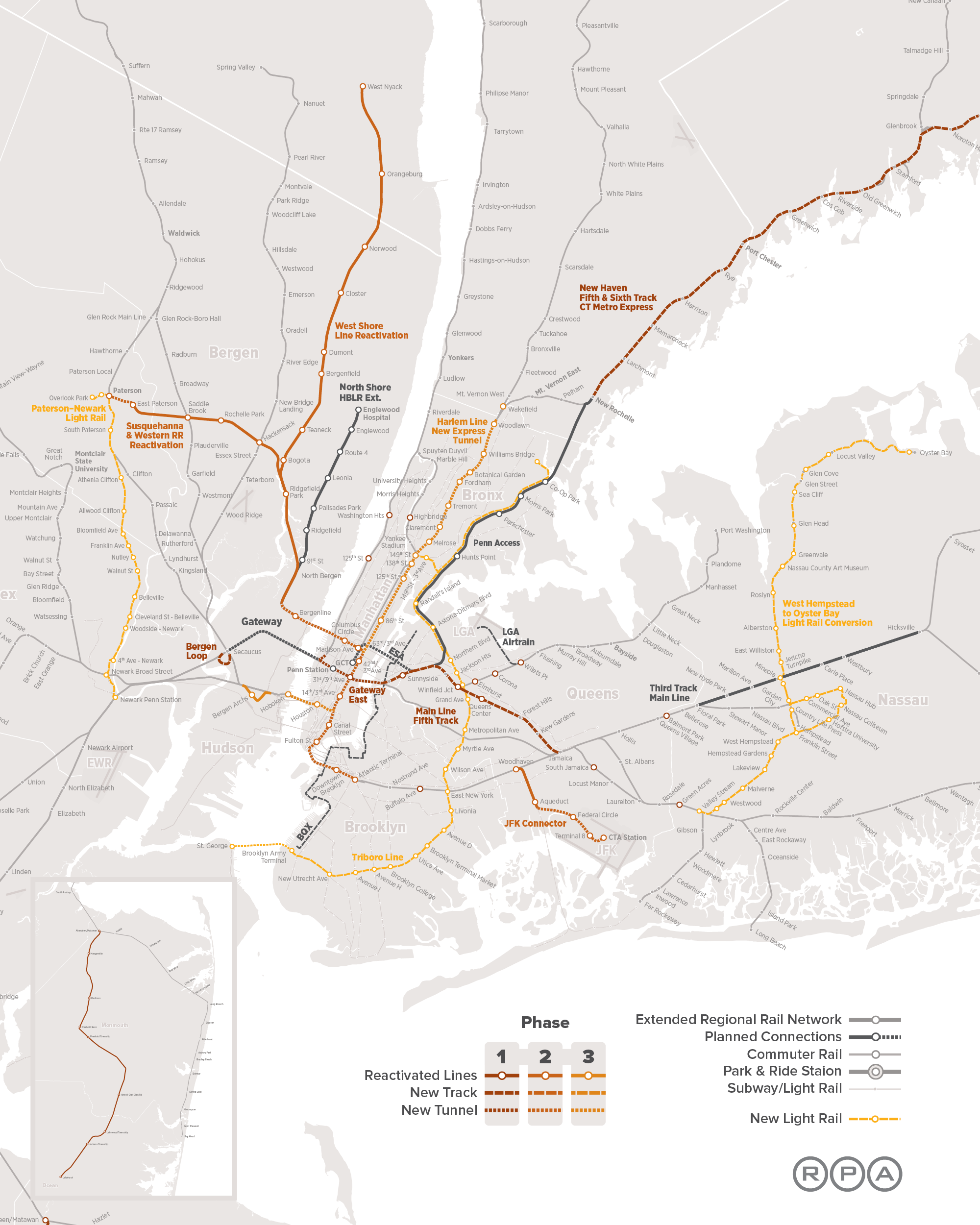

Based on an analysis of existing deficiencies, future demand, and project feasibility, a fully integrated regional rail system could be built in three phases.

Phase two: Additional trans-Hudson and east side service, and restored passenger service in northeastern New Jersey

Before 2040, it is expected that the Gateway/Crosstown tunnels will also be at capacity. And even though 2040 sounds like a long way off, planning and building infrastructure of this scale can take decades, so it really shouldn’t be too long before we begin to plan for the next set of trans-Hudson tunnels. Additional rail tunnels from Union City, NJ, to 57th Street in Midtown would provide the next trans-Hudson capacity expansion after Crosstown reaches full capacity. New tunnels at 57th Street would also allow for the restoration of passenger service on the West Shore line, a portion of the Northern Branch line, and the Susquehanna lines in Bergen, Passaic, and Rockland counties. These areas are almost exclusively served by express buses today. The completion of this portion of the system would likely reduce the demand for express buses significantly enough to enable the Port Authority to replace its current bus terminal with either a smaller Manhattan facility or bus intercept facilities in New Jersey.

Beyond providing new rail service to many New Jersey communities, this second phase of the proposed regional rail network would provide a new north-south transit service on the East Side of Manhattan from 57th Street, running south under Third Avenue, and making four to five stops to Lower Manhattan, a corridor that currently is only served by the Lexington Avenue subway. This service could obviate the need to construct the lower portions of the Second Avenue Subway. This “Manhattan Spine” would be connected to the Crosstown line via a new hub station located at 31st St and Third Ave, allowing a seamless transfer between the Crosstown and the new service that would run along 57th Street and down Third Avenue.

The Manhattan Spine would continue to run downtown, stopping at Fulton and Water Street, and then into Downtown Brooklyn, where it would connect with the Long Island Rail Road at Atlantic Terminal. This portion of the line would provide robust and speedy rail transit service to parts of outer Brooklyn and southeastern Queens, which currently have limited transit options. A short extension to JFK Airport would also be made using part of the existing Rockaway Beach Branch line, south of the Atlantic Branch, along with the construction of a short new segment with two new stations at the airport.

These investments would provide the following benefits:

- Transit capacity to support the continued expansion of the region’s economy

- Vastly improved service and much shorter travel times for residents of Bergen, Passaic, and Rockland counties

- Reduced crowding at Penn Station

- Elimination of the need to build a large bus terminal

- Possible elimination of the need for building the lower portions of the Second Avenue Subway

- Direct service connecting New Jersey, Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and JFK Airport

Phase Three: Completing a fully interconnected regional rail network

The final phase of constructing the regional rail system entails completing the uptown portion of the Manhattan Spine to connect to the Bronx, Westchester, the Hudson Valley, and Connecticut, and the lower trans-Hudson tunnels that would complete a “Jersey Loop” that connects to service in the north to Hudson County.

The Uptown portion of the Spine would provide relief for Metro-North’s Park Ave Tunnel, which currently runs at capacity. The completion of Penn Access, a project to add tracks and station on the Hell Gate line so that Metro-North Railroad’s New Haven line trains can directly access Penn Station, should reduce stress on the Park Avenue Tunnel, buying some time for Metro-North. But the project will not ultimately divert any riders bound for the East Side. The Uptown portion of the Manhattan Spine, however, would provide relief, paralleling the Park Ave Tunnel along Third Avenue, providing a new express track through the Bronx from Mott Haven to Woodlawn, and seamlessly connecting the Mid-Hudson and Connecticut into the new regional rail system.

The lower leg of the Jersey Loop will provide a third new set of trans-Hudson tunnels, reducing future congestion, improving access to Hudson County, creating opportunities for more direct travel within the region, and providing additional redundancy. The construction of this new tunnel could also serve as a replacement for the Uptown PATH, which has tunnels over a century old, small stations, an inefficient junction, and a terminal at Hoboken that limits capacity and performance and is costly to maintain. On the New Jersey side of the Hudson River, the tunnels will lead to a station at Hoboken/Newport and a new stations in Jersey City Heights via the Bergen Arches, eventually connecting into the existing NJ Transit system.

This expansion would allow for the complete unification of the regional rail network with the following improvements:

- Less crowding, improved reliability, and more service for Metro-North riders

- Direct access through Manhattan from Westchester, the Mid-Hudson, and Connecticut, to New Jersey and Long Island

- Transit service for Bronx residents in the Third Avenue corridor, which today has very poor transit access

- Direct access to JFK Airport from the Bronx, Westchester, Mid-Hudson, and Connecticut

- Expanded service for residents of Hudson County and reduced crowding for New Jersey Transit riders at Penn Station

- Elimination of the need to replace the PATH Uptown line

Provide frequent service in all directions

The physical connections described above would allow for transformative improvements to rail service. Instead of long wait times, passengers in the Bronx, Queens, Hudson, Westchester, and Nassau counties would have access to more subway-like frequencies—in both directions. Passengers in Bergen, Passaic, Monmouth, Hudson and Essex counties would have access to the rail network with consistent service. Finally, an intercity express service would offer faster speeds, lower fares and more direct service between major hubs—from New Haven to Trenton, and from Poughkeepsie to Ronkonkoma.

All of these services would be overlaid in a Trans-Regional Express (T-REX) system that combines the territories of all three commuter railroads, and complements and connects to the New York City subways and PATH.

In much of the region, the service would provide a consistent level of service: every 15 minutes throughout the day and every 10 minutes during the traditional peak periods. Such a schedule would reduce the physical stress placed on the system and allow it to be used throughout the day as a viable transit option.

The system could be managed either by combining the existing railroads into one operating agency, or by creating a regional coordinating entity that would be responsible for coordinating schedules, fares, and operations among the three railroads. The service could be operated by the existing public authorities or by private concessions, such as the London Overground.

Outcomes

The regional rail proposal would dramatically increase rail capacity across the Hudson River, provide additional layers of redundancy for the region’s transit system, and bring rail service to currently unserved areas of New Jersey. It would improve the region’s rail service by standardizing fares, headways, service routings, rolling stock, and transfer arrangements to create a coherent and integrated system. Travel times would be reduced from well over an hour to less than half an hour for many commuters, and traveling would be far more predictable. The system as a whole would be significantly more resilient with multiple options for rerouting service or taking alternative routes. As a result, the region would be able to attract and sustainably accommodate far more economic growth. Many residents who can’t reach or afford rail service today would be able to use it on a regular basis.

Paying for It

The system would be built out over several decades. The cost of the tunnel is likely to be in line with costs for other rail projects in the New York City region, although these costs are likely to change over the different phases of the project. Without reforms to bring down project costs, it will be nearly impossible to afford these improvements. However, implementing this regional rail program does provide opportunities for savings from economies of scale and standardized construction practices, and by obviating the need for other projects. For example, the regional rail system would result in a smaller bus terminal than currently planned, and could obviate the need for the southern portion of the Second Avenue Subway, saving tens of billions of dollars. The sources of revenue would need to include substantial federal revenue, as well as dedicated revenue from new sources, such as mileage-based fees for automobile and truck travel or carbon pricing that could provide revenue for a range of transportation projects.