A multitude of laws governing rates, assessments, exemptions, and valuations has left us with a backward structure in which the wealthiest people often pay the least taxes. It is not uncommon, for instance, for a longtime resident in a modest house in a working-class neighborhood to pay the same amount for property taxes as someone who has just bought a multimillion-dollar brownstone in Park Slope. A condo in Manhattan may incur the same property taxes as a condo that sold for 20 times more at the exact same time. Modest, rent-stabilized apartment buildings built 80 years ago can pay so much in property taxes that maintenance and upkeep can suffer, while apartment buildings built 10 years ago generally pay next to nothing. Properties owned by utilities are taxed at a very high rate, which gets passed on to everyone who pays an electric or water bill.

These irrational discrepancies stem from a broken taxing system that must be made fair. The New York City property tax structure features four separate tax classes, whose rates, valuation, and rules are largely determined independently of each other, resulting in imbalances. Various exemptions and policies have been instituted over the years to rectify these imbalances, such as a special tax reduction for co-op owners, and a large, long-term exemption to spur rental development. The result is a convoluted and unfair system that needs to be restructured.

Reform should aim to make property taxes more equitable without creating sharp, short-term tax increases for existing beneficiaries

New York City should reform its property tax structure following these principles:

- Base residential housing property taxes on actual value, not type of structure

- Reduce property taxes that have a disproportionately regressive effect on low-income residents

- Put in place mechanisms to make sure renters directly benefit from any reductions in property taxes

- Reform tax exemptions so that taxpayer costs are proportionate with public benefits provided

- Make sure reforms do not unnecessarily harm residents in the short term; move smoothly and steadily toward a more logical and fair system

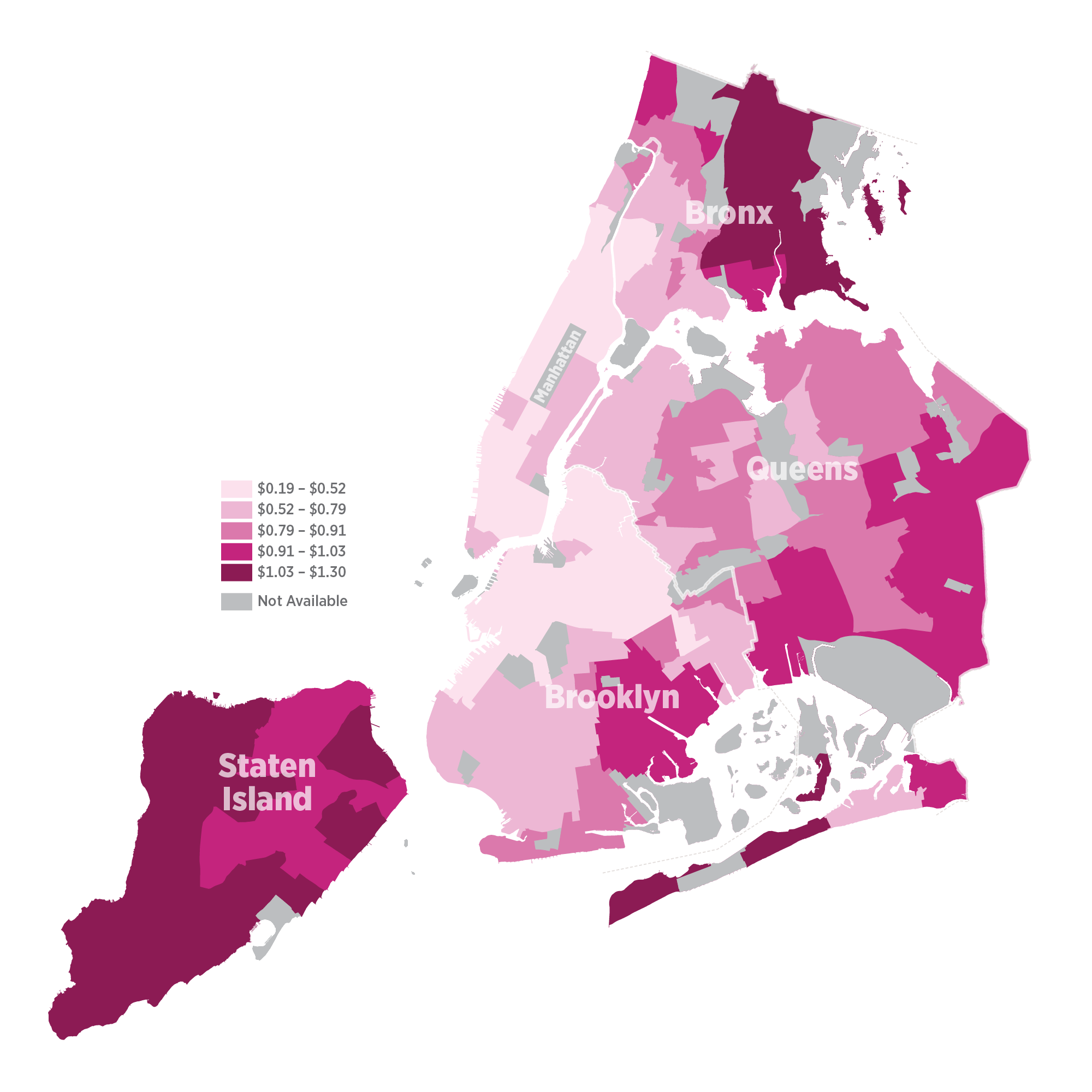

End the residential tax cap on title transfers

Assessed value increases for one- to three-family residential properties (Class 1) and smaller multifamily buildings (Class 2a, 2b, and 2c) are capped at a certain percentage every year in order to protect those who own properties in rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods from sharp bumps in property taxes. Because this cap is tied to the building, not the owner, it is passed on indefinitely, leading to property taxes in gentrified neighborhoods staying depressed over the long term compared with those in neighborhoods that have seen more modest price increases. These artificially low taxes also have the effect of inflating sale prices, giving an added benefit to owners in gentrifying neighborhoods and driving even higher price increases.

A more rational policy would be to tie the limitation on increases to the owner instead of the building, and end it after any part of the building transfers titles and the assessed value resets based on the current market value. This would still protect existing owners from sharp increases in property taxes, while also bringing practices in line with larger multifamily (Class 2) properties.

Equalize property tax methods between small and large properties

Buildings with either three or fewer residential units or four or more residential units play much the same role in New York City. Both are used for housing, and can be owned or rented. Yet, they are treated completely differently in the tax code. Valuation methods, assessments, tax rates, and tax caps are all calculated differently. Exemptions and abatements differ between the two types of property as well. For instance, cooperatives and condominiums have an abatement for owner-occupants, while one- to three-family homes do not. New York City should move toward a system in which small and large residential properties are treated similarly in terms of valuation, assessments, rates, caps, exemptions, and abatements.

Determine property values more accurately

The method by which multifamily properties today are assessed—according to their value as rental properties, even if they are owner-occupied cooperatives or condominiums—often leaves co-ops and condos valued significantly lower than their actual market value, especially at the high end of the market. More modest properties are therefore left to make up the difference with comparably higher taxes. A better way to value properties would be to use the same process as one- to three-family homes, which is based on the the actual sales value of comparable homes.

For rental properties, care must taken with this approach. Basing a building’s taxes on the sales or refinancing price of the building itself would likely have the effect of both reducing speculation and overleveraging, as speculative sales prices would be discouraged by the resulting higher tax bills. However, basing a building’s taxes on comparable sales prices would result in higher taxes for all buildings in areas of speculative price increases, which may exacerbate displacement pressures.

Institute a direct renter’s credit

The savings from any reduction in property taxes for rental buildings must be passed on at least partially to tenants, especially those who are low income. Without a direct method of delivery, these savings are not likely to be realized by tenants because of market and regulatory factors. And low-income tenants in one- to three-family homes should likewise be protected from rising rents that might come about as a result of higher taxes on the property. A direct mechanism, such as a refundable credit on state or city income taxes for renters, would ensure savings are divided appropriately between owners and renters.

Lower property taxes on utilities

Utility properties pay disproportionate real estate taxes on their holdings, accounting for 6 percent of all tax revenue while holding just 3 percent of the real estate value in the city. Since utilities are heavily regulated, this has the effect of a de facto regressive tax on all utility ratepayers, regardless of income. Capping or reducing these taxes would move the tax system overall in a more equitable direction.

Reform how multifamily and commercial exemptions are done

New York City offers tax exemptions and abatements to stimulate a certain kind of development or upgrade. Often times, however, most notably in the case of the 421a exemption for multifamily housing, instead of dedicating a set amount of money to stimulate development, the costs are left open-ended. The more a property increases in value, the greater the cost to the taxpayer.

These exemptions should be restructured to one in which a set amount of benefit is given and the value of the exemption is capped, which will ensure the public expense doesn’t exceed the public benefit.

As a result of this all-or-nothing system, buildings eligible for these exemptions often pay next to nothing in taxes for decades, regardless of how valuable they are. Other buildings—often older and less valuable—then have to pick up a disproportionate share of the tax burden. Just as buildings paying too much in taxes should see their tax burdens go down, buildings benefiting from overly generous exemptions should pay their fair share.

There are also large differences in taxes on commercial properties due to tax incentive policies, most notably the Industrial and Commercial Abatement Program. While commercial taxation rates should be set separately from residential rates, incentives should be examined to provide the proper balance of commercial and residential development.

Outcomes

Making New York City property taxes fair and effective would result in direct savings for low-income households, and a fairer and more rational structure for residential housing overall. It would likely also have the effect of lowering housing prices in high-end, owner-occupied housing due to re-sized tax bills.

Smart property tax reform would also generate more housing production by reducing the gap in tax burden between large residences and multiple smaller units, making it more financially feasible to build rowhouses or duplexes than large McMansions, and multiple smaller condominiums instead of large penthouse apartments.

Cutting down on large incentives for multifamily residential construction would likely have a temporary negative effect on housing production. In the longer term, however, reducing the overall tax burden for multifamily housing would encourage production.

Paying for it

These reforms could be specifically designed to be revenue-neutral, meaning the savings from tax increases on one type of property would be offset, dollar-for-dollar, by decreases on others types of property. Decisions about raising more or less revenue through property taxes overall would be unaffected by this proposal, and New York City would retain the ability to make those decisions based on current fiscal conditions.

Residents who would likely see higher costs are new owners of high-cost one- to three-family homes, as well as owners of high-end cooperatives and condominiums. Existing owners of these properties would likely see lowered property values because of the higher taxes upon sale. The people likely to see lowered costs would be rental tenants of existing, older multifamily housing. City residents as a whole would also realize savings through lowered utility costs.