High property taxes are one of the biggest complaints of homeowners, and a frequent target of legislators. And indeed, property taxes in the tri-state region are among the highest in the United States. As a share of home values, New Jersey has the highest property taxes of all 50 states, and Connecticut has the seventh highest rates. New York is 17th and would be higher were it not for New York City, which does not need to rely on property taxes because it levies income and sales taxes.

High property taxes are the result of a number of factors: choices of local officials and voters for types of services they want, inefficient service delivery that stems in part from a large number of small municipalities and school districts, and for many municipalities, the dearth of other revenue-source options.

Property taxes are a relatively stable source of revenue, and they are fair in the sense that property owners generally benefit from the services their taxes pay for. But when municipalities depend largely—and sometimes exclusively—on property taxes for revenue, it reinforces inequities between rich and poor communities. In less wealthy cities and school districts, municipalities make up for lower home values by cutting services and increasing property tax rates. As a result, many lower-income households end up paying a larger share of their incomes than households in wealthier communities—and often for worse service. Schools in poorer communities—where students have greater academic needs and require additional resources such as specialty teachers, equipment, and programs—have historically had the lowest budgets because they had less property tax revenue to support them. Meanwhile, schools in wealthier communities have had the highest budgets thanks to a big property tax base. Increasing state aid has narrowed this gap, but large differences between resources and needs remain.

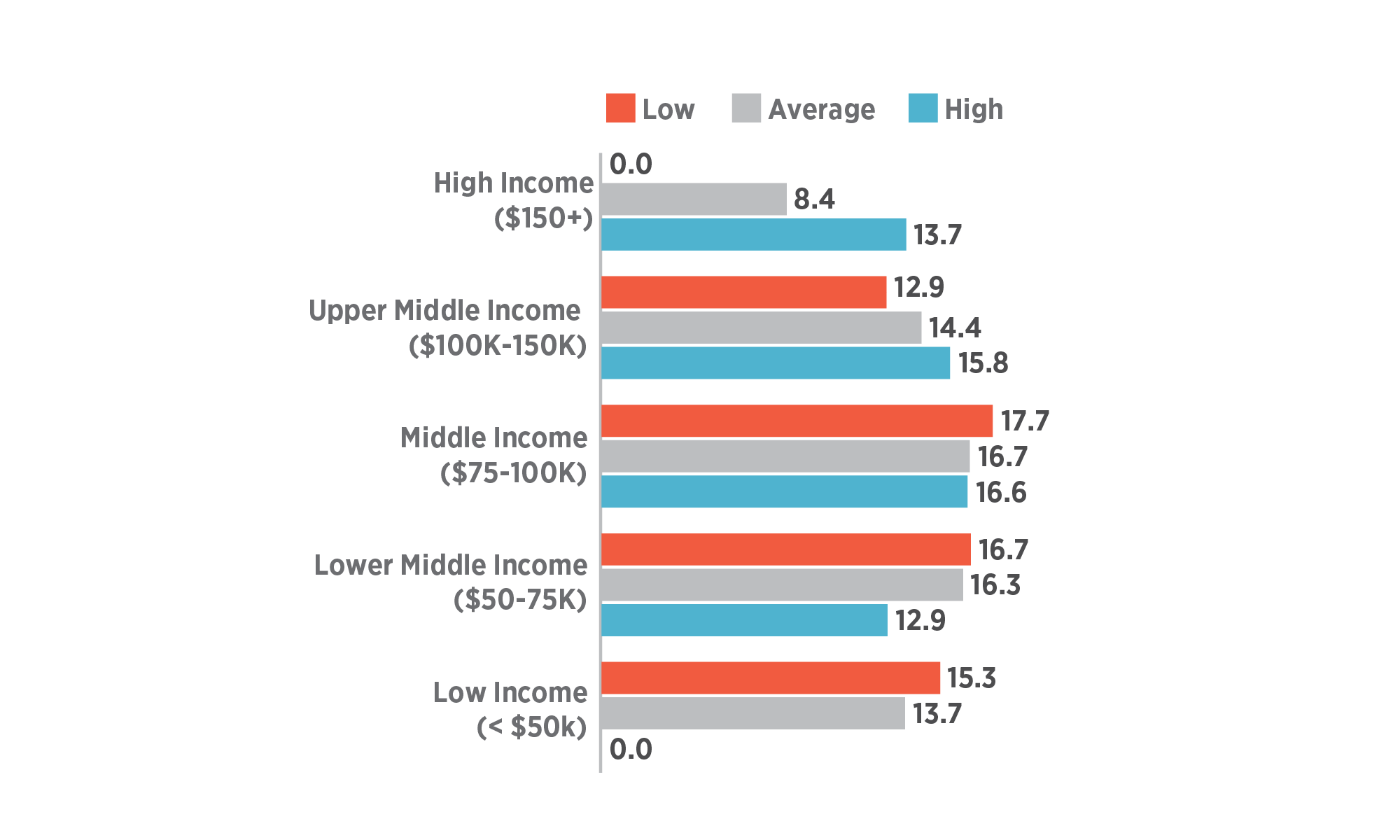

On average, homeowners in high-income school districts pay the lowest property tax rates and have the highest-achieving schools. Homeowners in low-income districts pay higher property tax rates for schools with the lowest test scores. Interestingly, it is homeowners in middle- and lower-middle-income districts who pay the highest school property tax rates.

Overreliance on property taxes also contributes to the region’s housing shortage. Communities often resist new residential development—particularly multifamily housing—out of fear that it will bring more children and add to school costs. Meanwhile, many studies have proven that multifamily housing does not add nearly as many school children as single-family homes (Joint Center for Housing Studies, Overcoming Opposition to Multifamily Rental Housing, 2007).

Local property taxes have also contributed to sprawl. Municipalities seeking to complement residential property tax revenue with commercial property tax and sales tax revenue have aggressively sought out the construction of new malls and retail development. Property taxes help explain why our suburbs are littered with large-footprint and underused commercial landscapes—aka, sprawl.

States have the power—and the responsibility—to address the problems with municipal property taxes

Even though municipalities levy property taxes, the ability to reduce inequities and inefficiency in the property tax system rests with the three states.

States should relieve localities of a higher portion of their school taxes

Over the last several decades, states have already taken a greater role in funding local schools, although usually under court order.

- New Jersey’s Abbott vs Burke case, for instance, mandated that the state provide the financial resources to ensure the students of 31 urban school districts—so-called “Abbott districts”—receive adequate public education, as required by the state constitution. Thanks to increased budgets, the performance gap between Abbott-district students and others in the state has narrowed (The Fund for New Jersey, Persistent Racial Segregation in Schools, 2017).

- New York State’s highest court made a series of rulings related to the Campaign for Fiscal Equity vs New York finding that the state school funding system was unconstitutional, and ordered the state to provide new funding to New York City’s public schools. Although some progress has been made, large gaps remain between urban and suburban schools.

- In Connecticut, building on the landmark Scheff vs O’Neill decision the required the state to address educational disparities in the Hartford area, a Superior Court declared in 2016 that the state’s gap in test scores between students in rich and poor towns, resulting from the state’s school funding system, was unconstitutional. The state’s Supreme Court will hear the landmark case in 2017.

Nevertheless, the overwhelming majority of property taxes paid by homeowners and businesses goes to fund local schools. And the overwhelming majority of municipal budgets is spent on schools. Even with increases in state funding, primary and secondary schools on average still receive over half of their funding from local sources in each state, with most of that coming from local property taxes.

States should increase their contributions to local school budgets, even if it means increasing state income or sales taxes, or perhaps imposing a statewide property tax. They could do so while requiring a commensurate reduction in local property taxes.

Shifting the tax base from municipalities to the state would make the overall tax system more efficient and equitable. Home owners in low- and middle-income districts would be less likely to pay higher taxes than owners in high-income districts. More education funding could be directed to the schools and students who are most in need. And there would be less incentive for towns and villages to try to stop the construction of affordable and multifamily housing or develop open space for low-density commercial space.

Provide incentives for service-sharing and consolidation

Local government is far more fragmented in the tri-state region than in other places in the United States. Outside New York City, there are 781 municipalities, 702 school districts, 491 fire districts, and dozens more authorities and special districts. Nassau and Suffolk Counties, for example, spend 45 percent more on public services and 60 percent more in property taxes than the comparably sized suburban counties of Fairfax and Loudoun in Virginia. Where northern Virginia had 17 county, town, city, village, and school district governments, Long Island had 239.

Sharing services or consolidating districts could generate economies of scale, deliver services more efficiently, and reduce property taxes. States are making some progress providing grants and technical assistance to municipalities that voluntarily share services, like fire equipment, school food, and transportation. But so far, results have been modest and diffuse. Evidently, it will take more aggressive measures from states to convince municipalities to coordinate. A new program in New York State, the County-wide Shared Services Initiative, is one approach that bears watching. It requires county officials to develop localized plans that find property tax savings from eliminating or coordinating duplicative services. Participating municipalities would be eligible for a one-time match from the state for demonstrated savings. It is too early to see results, but the requirement to develop a county-wide plan is a structure that could be enhanced and replicated.

In the longer term, states will need to provide more sustained incentives to achieve significant efficiencies. In cases of extreme inefficiency or inequity from small, fragmented districts, the state should make any state funding contingent on consolidation or an acceptable shared-services plan.

Give cities and counties the ability to diversify their revenue base

New York City and Yonkers have been authorized by the State of New York to levy income taxes. Allowing other cities, counties, and even larger towns and villages the ability to levy income taxes would lead to a more progressive tax structure and generate alternative revenue sources for communities with limited property tax bases. It would also make land-use decisions more rational by putting more emphasis on broader economic benefits rather than direct property tax ratables.

New York State also allows county and city sales taxes, whereas the other two states do not. Allowing counties and cities to levy sales taxes, while regressive, would be a means of broadening and diversifying the tax base. Municipalities would need to carefully levy the right mix of taxes to balance the revenue potential and volatility of taxes with their relative benefits.

States should also encourage municipalities to charge different property tax rates for the value of buildings than for the value of the underlying land. Taxing land at a higher rate than improvements encourages the development of vacant lots, brownfields, and underutilized properties, which could lead to more mid- to high-density, and more mixed-used development in downtowns and near transit. Where this model has been tried—in Pittsburgh, Scranton, and Harrisburg for example—more housing has been built and at greater densities than they likely would have with a traditional property tax structure.

Most of these reforms would not reduce the overall level of taxation, but would shift tax burdens to make the system fairer and more efficient. Shifting more of the costs of education to the state would lower everyone’s property taxes, but likely raise income, sales, and other state taxes unless the state chose to reduce spending or enact new types of taxes or fees. Municipalities and school districts with a low property tax base would benefit most. It would also increase funding to the schools and students who need it most. Sharing services and consolidation would reduce the overall level of taxation, or improve service quality, by making government more efficient. Providing municipalities with greater flexibility could provide more stability to local finances by broadening sources of revenue and helping to lessen tax burdens for households with low incomes but relatively high home values.

All of these reforms should lead to the creation of more and lower-priced housing by lowering resistance to multifamily and affordable housing and increasing incentives for owners to develop their properties. The reforms would also reduce incentives for allowing low-density commercial development—and thereby suburban sprawl—although market forces are making this less of an issue than it has been in the past.

Paying for It

Reforms should be revenue neutral in the short term and add to revenues in the long term by encouraging more multifamily and mixed-use development. Tax burdens would shift from lower- to higher-income households.

1. Tax-Rates.org, “Income Tax Rates by State,” 2017

2. U.S. Bureau of the Census, “2015 Public Elementary-Secondary Education Finance Data,” 2015

3. Long Island Index, “A Tale of Two Suburbs,” 2007

4. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, “The Effects of the Two-Rate Property Tax,” 2014