Educational achievement is one of the most important determinants of personal well-being, and a key to the success of the region as a whole. It is a strong predictor of personal income, upward mobility, health, and longevity—and increasingly separates prosperous from declining metropolitan areas. Unfortunately, the large gap in achievement levels that stems from a long history of inequities for poor, black, and Hispanic families is a crisis for the region as well as the nation.

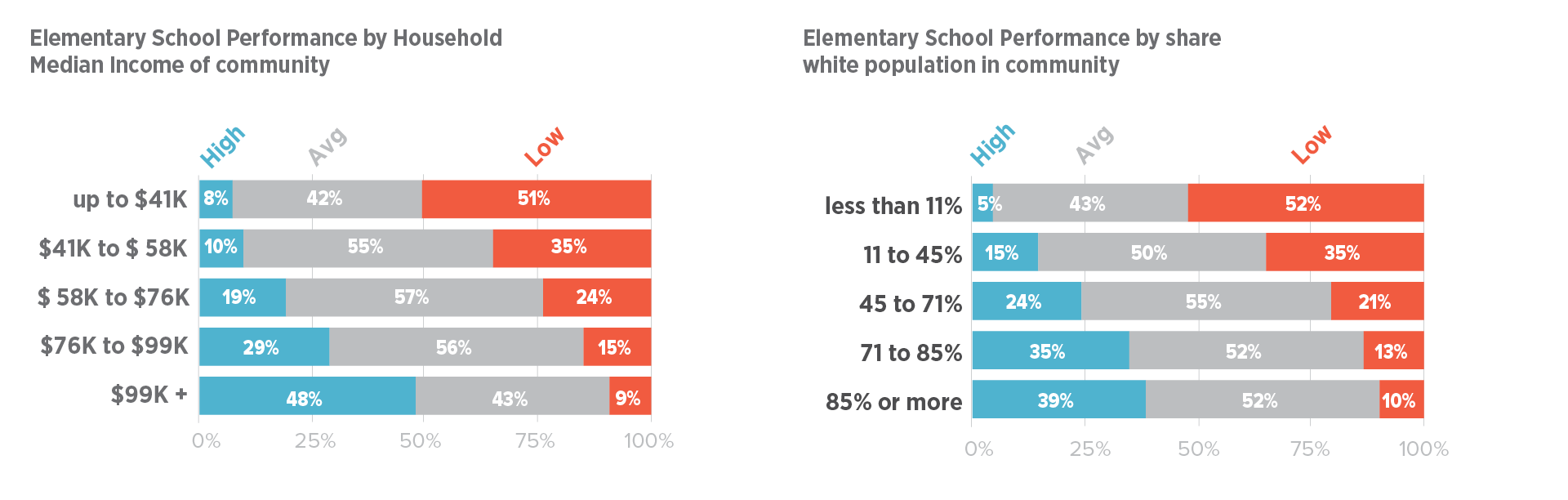

While educational outcomes are determined by many factors, including prenatal care and neighborhood conditions, the type and quality of schools can make the difference between success and failure. In the tri-state region, half of the elementary schools in predominantly low-income and non-white communities have low academic achievement when measured by fourth- and eighth-grade test scores, and only a small percentage are among the highest achieving. Test scores do not necessarily reflect the quality of instruction or leadership, but they are the best available indicator for comparing school outcomes across the region. And there is ample evidence that low-income and non-white students who attend high-achieving and integrated schools perform better than those who attend low-achieving, segregated schools, and that higher income and white students benefit as well.

In all three states, the large number of school districts reinforces segregation, creates inefficiencies, and unfairly distributes property tax burdens.

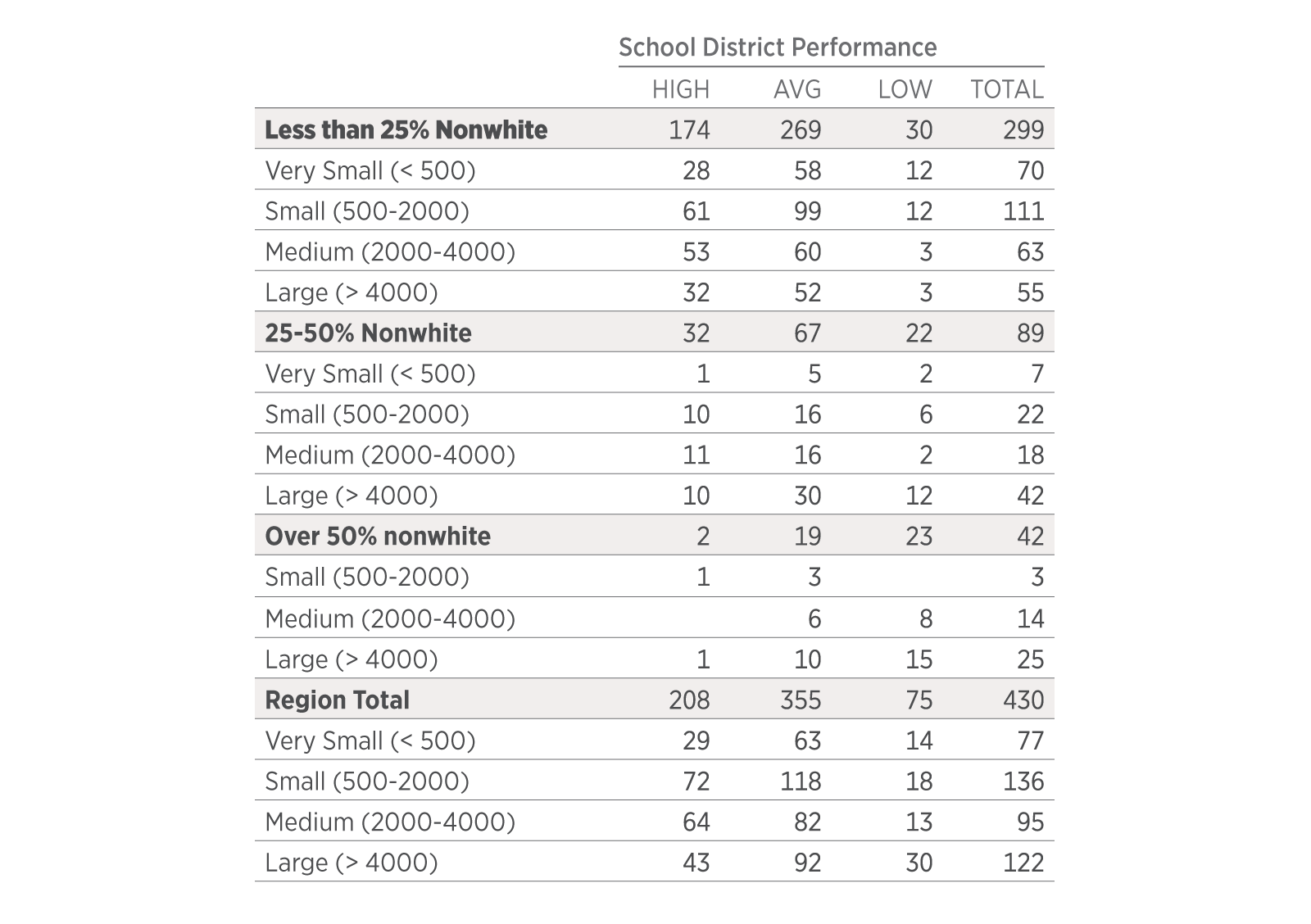

More than three million students attend school in 686 school districts across the tri-state region. Half of these districts have fewer than 2,000 students, and 113 have fewer than 500 students. New York and New Jersey have some of the highest numbers of small school districts in the country that are in close proximity to each other.

By many measures, these small school systems are among the most racially and economically segregated in the United States. New York is the most segregated state in the nation when ranked by the exposure of black students to white students, and New Jersey and Connecticut rank sixth and 14th, respectively. By a broader measure, school segregation on Long Island is twice the national average.

The segregation of our school districts is largely due to school districts being determined by municipal boundaries, with most people in the region living in segregated communities. As a result, most of the region’s poor and non-white students are concentrated in large urban districts, while white students predominate in small suburban and rural districts.

A recent study found that, on Long Island, schools within the same school district were similar to each other, but schools in different districts were significantly different from each other, segregated by school district boundaries. A different study found that segregation in New Jersey was driven by school district boundaries, which are largely coterminous with municipal boundaries.

Fragmentation also means many services cost taxpayers more than they should. Larger districts benefit from economies of scale, and therefore pay less per student for superintendents, teachers, administrative staff, transportation, and supplies than smaller districts, often without sacrificing the quality of the education.

States should provide incentives to integrate schools and combine school districts

Outcomes

Each state should set a goal of increasing the number students attending high-performing, integrated schools. A reasonable goal would be to bring school segregation to the national average in 15 years, and provide direction, support, and incentives for school districts to collaborate to meet that goal. The Hartford program and other models have proven that the gap between poor and affluent students and non-white and white students in reading scores, graduation scores, and other achievement measures can be reduced substantially and in a relatively short period of time.

Paying for it

The most expensive element of a regionalization strategy would be the creation of regional or magnet schools. They require substantial investments and programs that both provide support for low-achieving students and attract high-achieving students. Connecticut has spent $1.4 billion to build and renovate its magnet schools and $150 million to operate them each year. But this approach also has the advantage of being voluntary for families and students. School consolidation and other approaches also require upfront administrative costs, but should save money in the long term by achieving economies of scale and reducing costs per pupil.

1. National Center for Education Statistics, “Monitoring School Quality,” 2000

2. The National Coalition on School Diversity, “School Integration and K-12 Education Outcomes, Brief No. 5,” 2011

3. The Century Foundation, “Hartford Public Schools,” 2016

4. Center for American Progress, “Size Matters: A Look at School-District Consolidation,” 2013

5. Civil Rights Project, UCLA, “Brown at 62: School Segregation by Race, Poverty and State,” 2016

6. Long Island Index, Rauch Foundation, “Inter-District and Intra-District Segregation on Long Island,” 2012

7. The Fund for New Jersey, “Persistent Racial Segregation in Schools:,” 2017

8. The Fund for New Jersey, “Persistent Racial Segregation in Schools: Policy Issues and Opportunities to Address Unequal Education Across New Jersey’s Public Schools,” 2017

9. ibid

10. ibid