The Amtrak line between Washington D.C. and Boston via New York City, known as the Northeast Corridor, is by far the busiest in the country. But, because of high ticket costs, slow speeds, and unpredictability in service, it is still barely competitive compared with driving and air travel. In fact, the NEC is far slower and less reliable than intercity train service in any other major region around the world.

Decades of underinvestment are largely to blame—as is Amtrak’s having to share the tracks with commuter railroads and freight trains. There are several major bottlenecks with insufficient capacity to accommodate all users. Fares are relatively high—unaffordable for many—as a result of Congress requiring Amtrak to be financially self-sufficient at the national level, and service on the NEC being used to subsidize routes with lower riderships in other parts of the country.

Both policy changes and physical investments will be required to create fast, reliable, and affordable service in the NEC

The Northeast Corridor, which extends from Virginia to Massachusetts, represents one-fifth of the U.S. economy. A functional intercity rail system would bolster the national economy and help keep the tri-state area economically competitive. But creating fast, reliable, and affordable service on the NEC will require both changes to the way Amtrak is governed and major investments in infrastructure over the next two decades.

- Reform the NEC governance and operating model to include a public authority that would control the corridor’s infrastructure and grant concessions to private operators. The model is similar to the UK rail system where Network Rail is the national infrastructure operator and the Department for Transportation grants operating concessions to private service providers. This would keep the public in control of the asset and long-term planning, but create incentives for more efficient operations.

- Stop using NEC revenues to cross-subsidize the national rail system, which starves the NEC of funds to improve capital assets along the corridor and provide a balanced fare policy.

- Upgrade infrastructure and address major bottlenecks, including $21.1 billion in state-of-good-repair backlog needs (moveable bridges, power, etc.) and billions more to address existing bottlenecks where limited tunnel capacity, at-grade junctions, and other physical conditions constrain throughput and reduce reliability.

- Increase frequency of service and lengthen trains. Intercity trains are six to eight cars, versus 10 to 14 cars for commuter trains. Making these trains longer and adding more trains per hour would substantially increase the supply of service along the corridor. Creating uniform rolling stock for intercity service would simplify operations and combine first, business, and coach classes on one train. To support the recommended increase in service, new crossings will be needed at the region’s core across both the Hudson and East rivers.

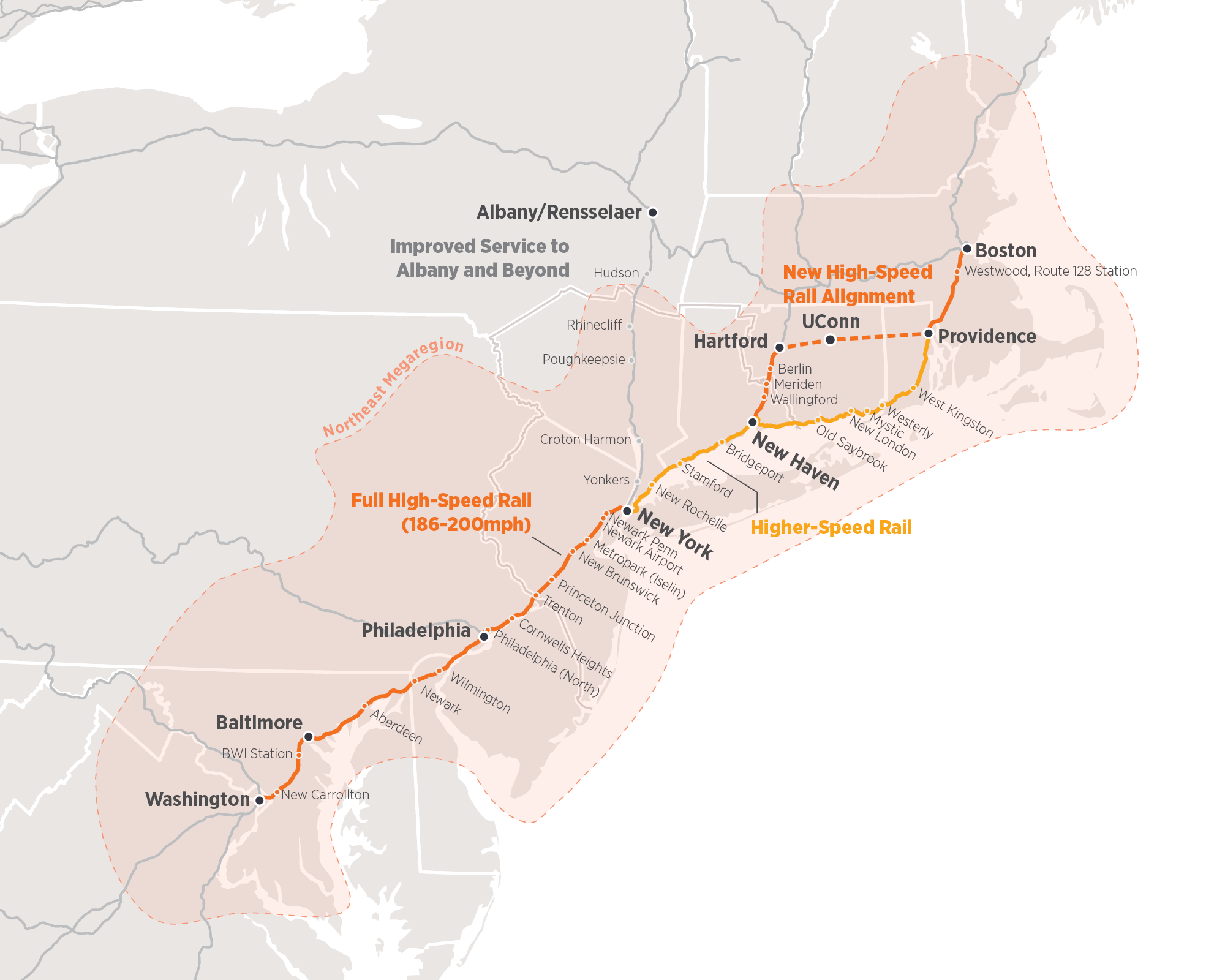

- Introduce a high-speed rail service between New York City and Washington D.C. To substantially improve service over the next 20 to 30 years, two new tracks dedicated to high-speed trains traveling in excess of 200 mph should be added. In the long term, new stations in Philadelphia and Baltimore will be needed to speed up service through those two metropolitan areas and to help reduce NYC to DC travel times to 90 minutes from the current 175 minutes for Acela, and 200 minutes for regional service.

- Substantially upgrade service from New York City to Boston. Aside from addressing a handful of critical bottlenecks, two major investments will be required to improve service between New York City and Boston. The first is two new tracks between New Rochelle and Barnum Station in Bridgeport, to support increasing intercity service frequency between NYC and BOS while also adding intra-state service and more traditional commuter services to NYC. The second investment needed is new intercity express alignment between New Haven and Providence via Hartford, to increase speed and improve resilience.

This leg of the NEC is unable to support true high-speed service (186 mph and above) due to the physical rail alignment and insufficient separation between track centers. Alternatives include the two “off-corridor” alignments proposed by the Federal Railroad Administration in its NEC Future analysis. The preferred alternative is to use the existing corridor, which would support economic growth in cities in a high-density corridor along the New Haven line.

- Explore options to improve service to Albany and points north, including Albany service out of Grand Central run by Metro North. Improvements could include electrification to Albany with better transit access to destinations between Albany and Poughkeepsie. Another option to consider is overnight trains to Montreal and Buffalo: Little new infrastructure aside from rolling stock (sleepers) would be required, and scheduling could open up access to popular destinations such as Montreal and Niagara Falls.

Outcomes

The proposed recommendations would dramatically transform intercity rail service, and result in the following outcomes:

- Higher frequency and faster service that would improve access to job opportunities for residents of the region. Regional service between NYC and Philadelphia would be faster than existing commuter service between Stamford and NYC.

- A more affordable and reliable service would divert more intercity auto, air, and bus travelers to rail. This would free up highways for freight and local traffic, and airports for longer-haul flights.

- Higher capacity on the NEC would allow for simultaneous growth in commuter, regional, and intercity services.

- Greater accessibility and more convenient scheduling could draw more riders to other (non-NEC) intercity routes.

Paying for It

Funding for NEC improvements would come from conventional sources such as federal grants and loans, and expanded local contributions—a mixture of track fees and passenger ticket surcharges. Additional funding/financing might be possible from public-private partnerships, with firms acquiring equity in the infrastructure as part of investing in modernization and capacity improvement, or as part of an operating concession. A return on investment is possible today due to the higher fares charged on the NEC.