The Port of New York and New Jersey is the second largest seaport in the nation, handling over six million containers and millions of tons of bulk cargo annually. But the port’s facilities are inefficiently managed. Terminals are not state of the art, and little investment has been made in the new technologies that would allow for reductions in air and water pollution. Lack of automation and outmoded management practices have kept labor costs high and reduced the port’s output. Connections to roadway networks are inadequate, and nearby roadways are often congested. While other ports around the country turn a profit, the Port of New York and New Jersey barely breaks even—at times even requiring a subsidy. The port’s deficiencies are enabled by a governance structure that provides insufficient transparency and incentives for efficient operations.

The Port of New York and New Jersey also sits in the middle of one of the densest rail networks in North America, yet hardly any of the region’s freight is moved by rail.

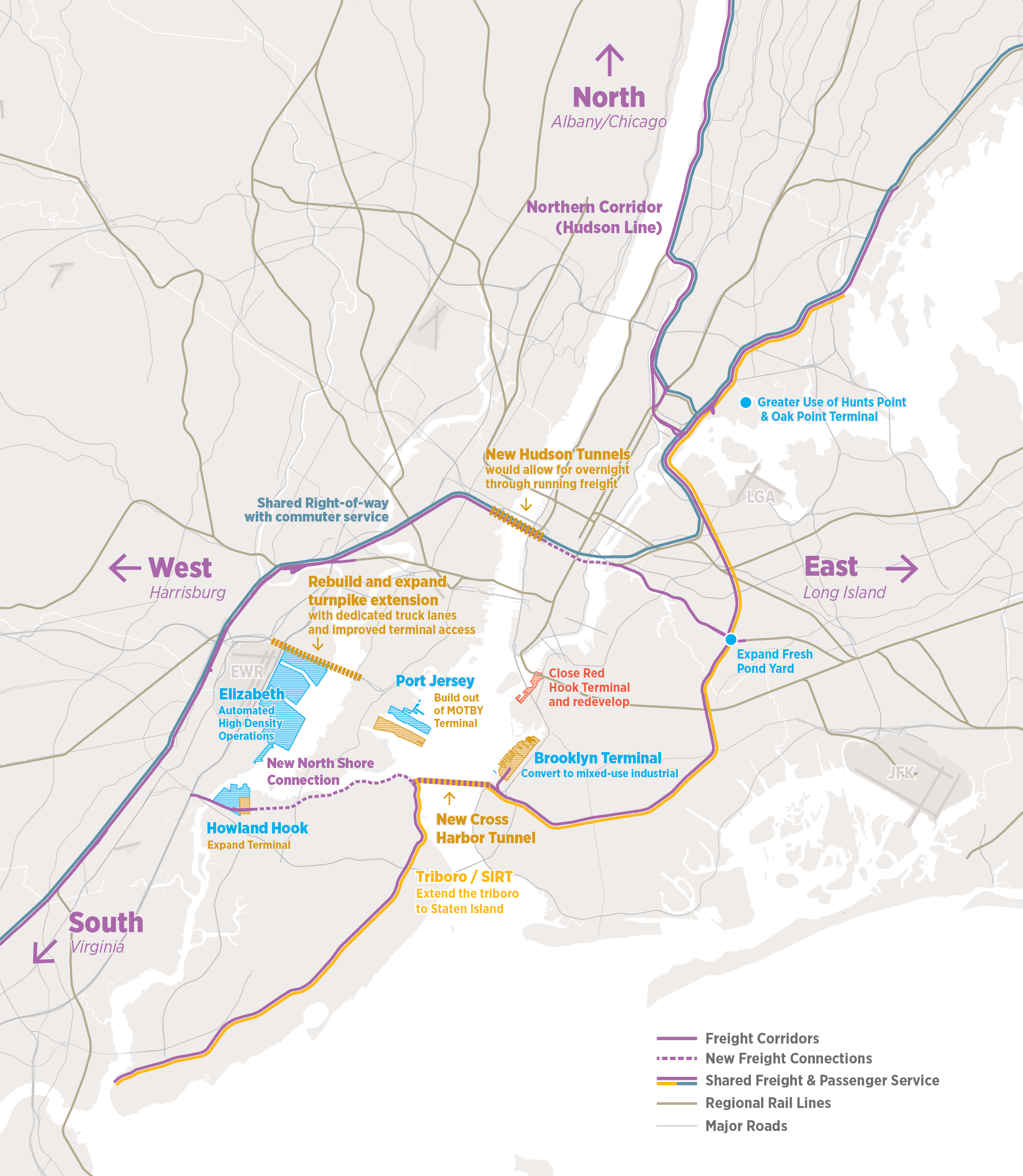

Nearly all the goods imported through the seaports are carried to their final destinations by truck, despite record congestion on roads and highways. Freight rail could provide a more reliable and efficient alternative—a single freight railcar can eliminate four truck trips—especially given the dense concentration of rail infrastructure in the tri-state area. But there are few rail lines dedicated to freight, and passenger rail operators typically refuse to allow freight operations on the busier parts of their network. The result is a segregated and underused rail network.

Modernize, rationalize, and expand our seaports

Transforming our seaports into 21st century facilities and turning a profit will require physical investments and governance changes, including:

- Reform the governance of the seaports to incentivize greater efficiency and modernization of the infrastructure. This could be achieved by giving the seaports greater operational and financial autonomy from the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, increasing transparency and accountability within the ports.

- Close and redevelop both the Red Hook container terminal and the southern Brooklyn (Sunset Park) seaport facilities. Both of these facilities are outmoded and have poor links to transportation. Their operations should be consolidated to ports in Staten Island and New Jersey, freeing up land for new parks, housing, and light industrial uses.

- Expand Staten Island’s New York Container Terminal to include the long-planned Port Ivory redevelopment. The port is well connected to the highway and rail networks, especially with the recent completion of the new Goethals Bridge. The direct ramps from the bridge to the port that have been proposed should be built.

- Modernize and improve access to Port Newark—Elizabeth Marine Terminal. The port should be densified, from five container stacks to seven, and its efficiency increased. More automation will enable it to increase throughput and revenue. Local road access should be improved to all facilities, including preferential treatment for trucks.

- Prepare Bayonne Peninsula for growth. In 2010, the Port Authority bought 130 acres in Bayonne for a mix of residential development and future port use. As part of this initiative, truck access to the peninsula must be improved by rebuilding and expanding the NJ Turnpike extension and interchange—a long-delayed project. The residential developments being built adjacent to the future port should be designed for a soft, transitional edge between residential and industrial uses. The Port of Los Angeles has done this successfully.

- Protect seaports and surrounding critical infrastructure from sea-level rise and storm surges. By virtue of their operating requirements, seaports are already fairly resilient. But with additional investments, ports could be designed to serve as buffers to help protect other vulnerable infrastructure nearby. Port Newark—Elizabeth Marine Terminal, for example, could help protect Newark International Airport and the I-95 corridor.

- Reduce noxious impacts to adjacent communities. Ships, on-dock equipment, and trucks are all sources of air, noise, and light pollution. The ports should provide shoreside electrical power to docked ships, allowing them to turn off their polluting engines. All the gantry cranes that have not yet been electrified should be. Only electric vehicles should be used for container movements within the ports. The Port Authority should take aggressive steps toward cleaner trucks—expanding the truck-replacement program, requiring low-emission vehicles as a default, and ultimately mandating a transition to electric trucks once they’ve become commercially viable. Light and noise abatement programs should be expanded, and measures should be taken to create transitional areas around the ports to buffer communities from those impacts.

Reduce truck traffic by promoting the use of rail for freight

Outcomes

These proposals would result in a modern and efficient seaport that would be a good neighbor to surrounding communities and return a profit to the public to invest in other regional infrastructure investments. They would also encourage the diversion of more goods to rail by sharing freight and passenger assets.

Paying for It

The new investments would be partially paid for by reforms requiring renegotiated leases or assessments on lease-holders for capital investments. Another source of funds would come from the redevelopment of surplus facilities, such as Red Hook. The Port Authority should assess whether an outright sale or long-term land lease is the most viable option. Track/tunnel access fees paid by the private railroads could also help fund the capital improvements and would be a source of revenue to maintain the infrastructure over the long haul. Traditional funding sources from the federal government, like Railroad Rehabilitation and Financing (RRIF) loans should also be pursued.