The Meadowlands has embraced its identity as a new kind of park that is not a pristine landscape, but a compelling demonstration of how vital natural systems services—habitat, flood control, clean water—can be reconciled with the infrastructure that is essential to the region’s prosperity. Through a balanced approach of protection and retreat, Meadowlands communities are thriving, healthy, mixed-use centers of activity, protected from storm surges and sea-level rise flooding, and connected to the restored beauty and biodiversity of a new model of national park that grows as the climate continues to change. Places like Secaucus are protected from rising waters, while smaller communities, like Teterboro and its airport, are returned to nature where floodwaters can be absorbed. Communities on the edge of the Meadowlands, on higher ground, are more dense with a greater mix of uses. The region’s job-rich warehousing and distribution centers are reconfigured and consolidated, becoming more vertical and aligning along a regional industrial corridor of roadways and rail lines. Vital infrastructure, including major roadways, rail lines, and wastewater and energy facilities is protected and elevated where necessary, ensuring this critical juncture keeps the region moving and thriving.

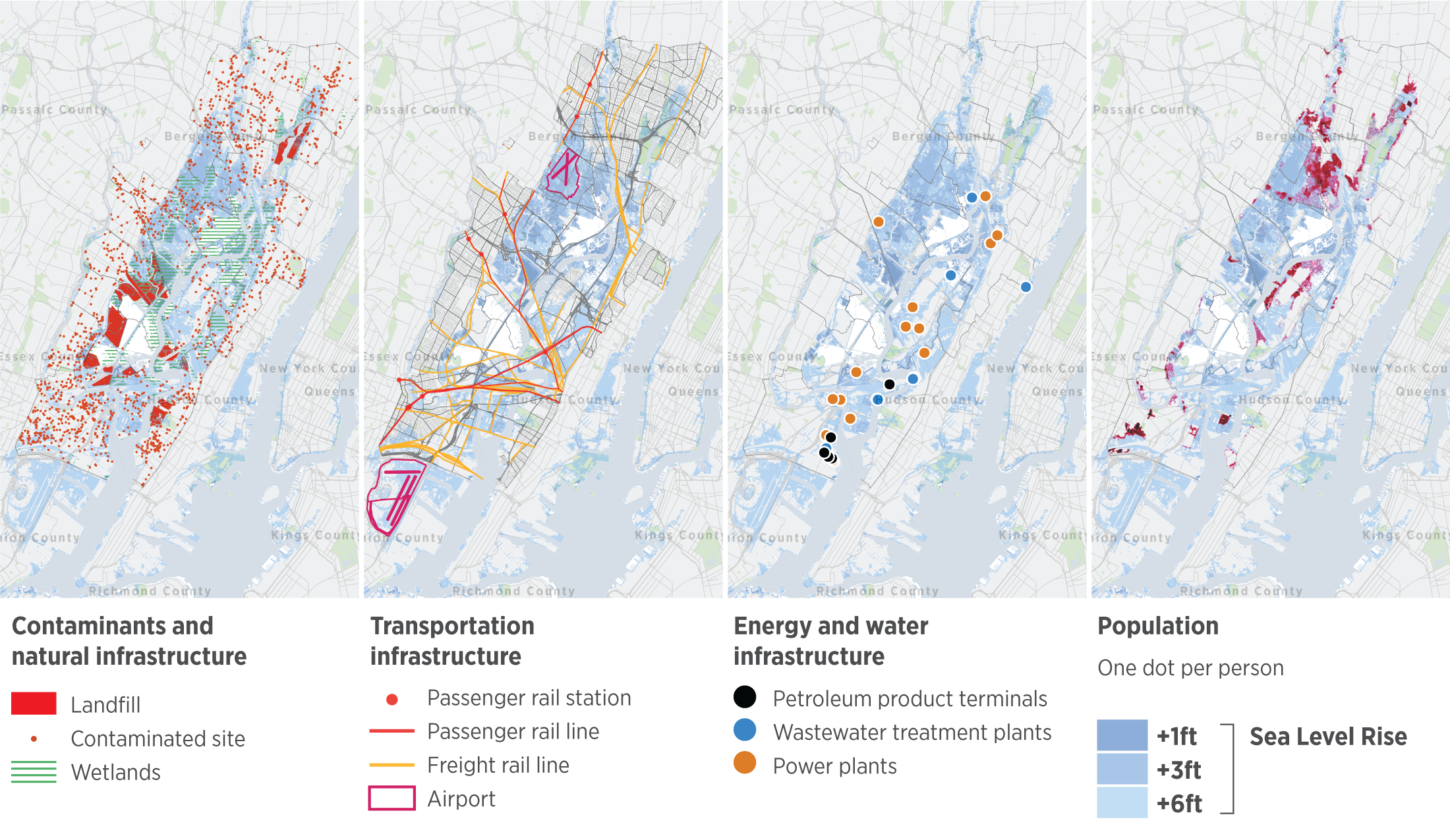

Over the past century, the New Jersey Meadowlands has been a distributed mix of communities and employment centers located in a significant, though compromised, estuarine system. The Meadowlands was also burdened with freight, commuter, and inter-city rail lines; and roads, power lines, refineries, and distribution and warehousing facilities that kept the northeast megaregion thriving. It was also home to some of the greatest concentrations of contaminated sites in the country.

Of all of the places in the region at risk of increased flooding from climate change, the Meadowlands presented perhaps the greatest challenge of all. In addition to threatening the infrastructure and natural systems described above, permanent flooding from sea-level rise was becoming a real risk for up to 36,000 residents and up to 51,000 jobs,1 while periodic flooding from increased precipitation and storm surges had threatened to disrupt the lives of 40,000 residents.

As the consequences of climate change (greater precipitation, more frequent and intense storms, sea-level rise, and extreme heat) began to accelerate, natural and human communities as well as vital infrastructure began facing greater risks, with few plans for addressing them.

Transforming the Meadowlands into the climate-proof, natural, and economic amenity has taken vision, cooperation, and significant investments. First, the concept of a new model for a national park—where park boundaries expand as the sea level rises and communities recede from the water’s edge—was tested and applied. An initial 10,000 acres of parks, protected wetlands, vacant land, and landfills were transferred from state, local, and land-trust ownership to the federal government. The 872-acre Teterboro Airport site was abandoned by the Port Authority and engineered into a natural flood storage site. A robust buyout program was created for the Meadowlands and vulnerable residents took advantage, selling their homes ahead of the coming flood and adding acreage to the growing park. At the same time, federal and state investments into cleanups of contaminated sites quickened, along with restoration efforts, and these former hotspots became educational features of the new park.

On the periphery of the Meadowlands, on higher ground, nearby towns saw the opportunity presented by the buyout program and national park and rezoned areas of communities for increased densities and mixes of uses. These border towns have become thriving, mixed-use suburbs with direct access to an environmental and recreational amenity.

The region’s Adaptation Trust Fund was tapped to invest in protective measures for those places with the greatest concentrations of population, employment, and critical infrastructure to guard against sea-level rise, storm surges, and heavy precipitation flooding. The town of Secaucus sits at the center of such an area, with the highest population of any single town in the Meadowlands, and is now a thriving suburban center. A new master plan for the area around Giants Stadium includes investments into flood protection and the phasing in of mixed uses. New Jersey Transit, the Port Authority, CSX, and the New Jersey Turnpike Authority have begun the complicated process of elevating rail- and roadways.

Private warehousing and distribution companies, and their tens of thousands of jobs—aided by federal and state economic development grants—joined together to relocate into concentrated, protected areas with good access to road and rail. These new vertical facilities represent a new model for the industry.

The dramatic changes taking place in the Meadowlands were only possible because of strong and forward-looking leadership provided by a Regional Coastal Commission, focused solely on the issue of adaptation. Members of the commission from all three states recognized the critical regional link the Meadowlands provides for roads, railways, and energy infrastructure, and could reach agreement on funding from each state’s Adaptation Trust Fund to ensure the region remains connected and thriving.

At the same time, the concept of a new model of National Park captured the imagination of residents and regional stakeholders, who were able to galvanize support at all levels and push through the formal state and federal processes. Municipalities at the greatest risk of permanent flooding were able to develop a timeline and begin participating in an innovative buy-out program to justly transition development away from the flood zones, knowing their former home would be part of a new park and natural habitat.

Communities surrounding the park were well-prepared to capture the economic and other benefits of this new amenity. Development around the edges of the park increased dramatically, due to transit and road connections. The Meadowlands was also able to maintain its role as a distribution and warehouse employment center by consolidating industrial uses into modern and resilient facilities.