More and more, housing and office development is encroaching on areas formerly reserved for industrial uses. To maintain industrial activities of all kinds—from essential services such as power plants, waste-transfer stations, and goods-distribution centers to more diverse manufacturing opportunities that support the larger creative economy—they must be modernized, made environmentally sound, and provide the amenities high-value businesses need. This requires new policies concerning workforce development, real estate, and urban design that are uniquely tailored to local contexts and the needs of residents and the economy.

Less than 2 percent of the region’s land is devoted to industrial uses, but that number is steadily decreasing. In high-value areas in Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and Hudson County, the main reason for industrial job losses is the land zoned for industrial uses is steadily being converted to housing, offices, stores, and institutions. Even where manufacturing is thriving or facilities are serving important functions, industrial land values are no match for the high prices residential and commercial uses can command.

This loss of industry in the core of the region has important repercussions. Having warehouses, waste management, and electricity generators located at the periphery of the region increases truck traffic, pollution, and transportation costs. It also exacerbates the decline in manufacturing employment, thus reducing economic diversity and limiting access to living-wage jobs. While automation and national economic shifts are partly responsible for the decline of manufacturing in the core of the region, high rents and a shortage of suitable space also constrain its growth.

In smaller, formerly industrial cities, the problem is different. There, many industrial areas have been abandoned as the kinds of spaces needed for manufacturing processes have changed. Because land values don’t justify the costs of environmental remediation, post-industrial lands become brownfields that disproportionately burden poor communities and communities of color.

Across the region, a further challenge to industrial lands is climate change and sea-level rise, as they are so often located at the water’s edge.

The region could retain a million industrial jobs over the next 25 years if the land and infrastructure is made available, and with the right investments in workforce development. A thriving industrial sector provides the essential services that make our homes, offices, stores, schools, and hospitals run, in addition to well-paying jobs that don’t require a college degree.

Maintaining a healthy industrial sector requires a range of strategies to reflect the needs and opportunities of the region’s diverse places of production, from urban manufacturing districts to suburban industrial parks, as well as exurban warehouses, distribution centers, and food hubs. Each requires a different approach to improve their functionality and competitiveness, and to regulate redevelopment from competing non-production uses such as mixed-use redevelopment, open spaces, and flood protection.

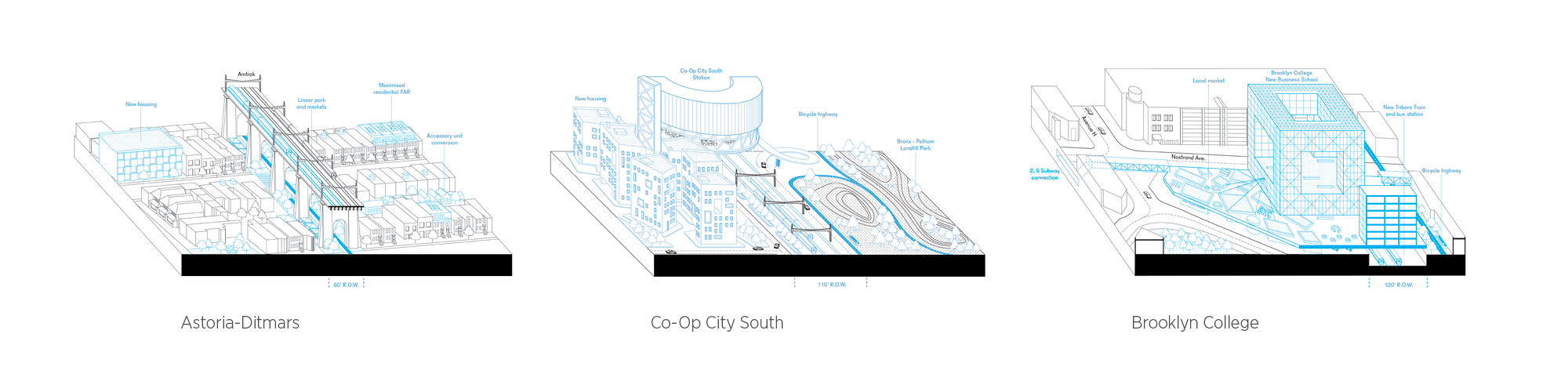

Industrial land is under the greatest pressure in the region’s urban core—including most of Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx, and large portions of Hudson and Essex counties in New Jersey. About 35 percent of the region’s industrial employment is in the core, where industrial job densities of 87 jobs/acre are several orders of magnitude higher than elsewhere in the region. Active industrial districts, such as the Industrial Business Zones in New York City and urban industrial parks elsewhere in the core should be protected from displacement. Essential improvements should be made to infrastructure and open spaces that affect the quality of the working environment. At the edges of these districts, design guidelines can manage the transition in scale and activity to the adjacent neighborhoods.

Traditional manufacturing neighborhoods present an opportunity to combine policies that protect industrial uses with new forms of live-work mixed-use development. This can support naturally occurring “innovation districts”—places where product innovation is supported by institution-sponsored research, allied design professions, and high-value-added manufacturing such as medical equipment or electronic components. These places need to be supported by flexible but targeted regulations that preserve industrial employment, high-speed internet, and ongoing support for local partnerships between research institutions, government, and industry.

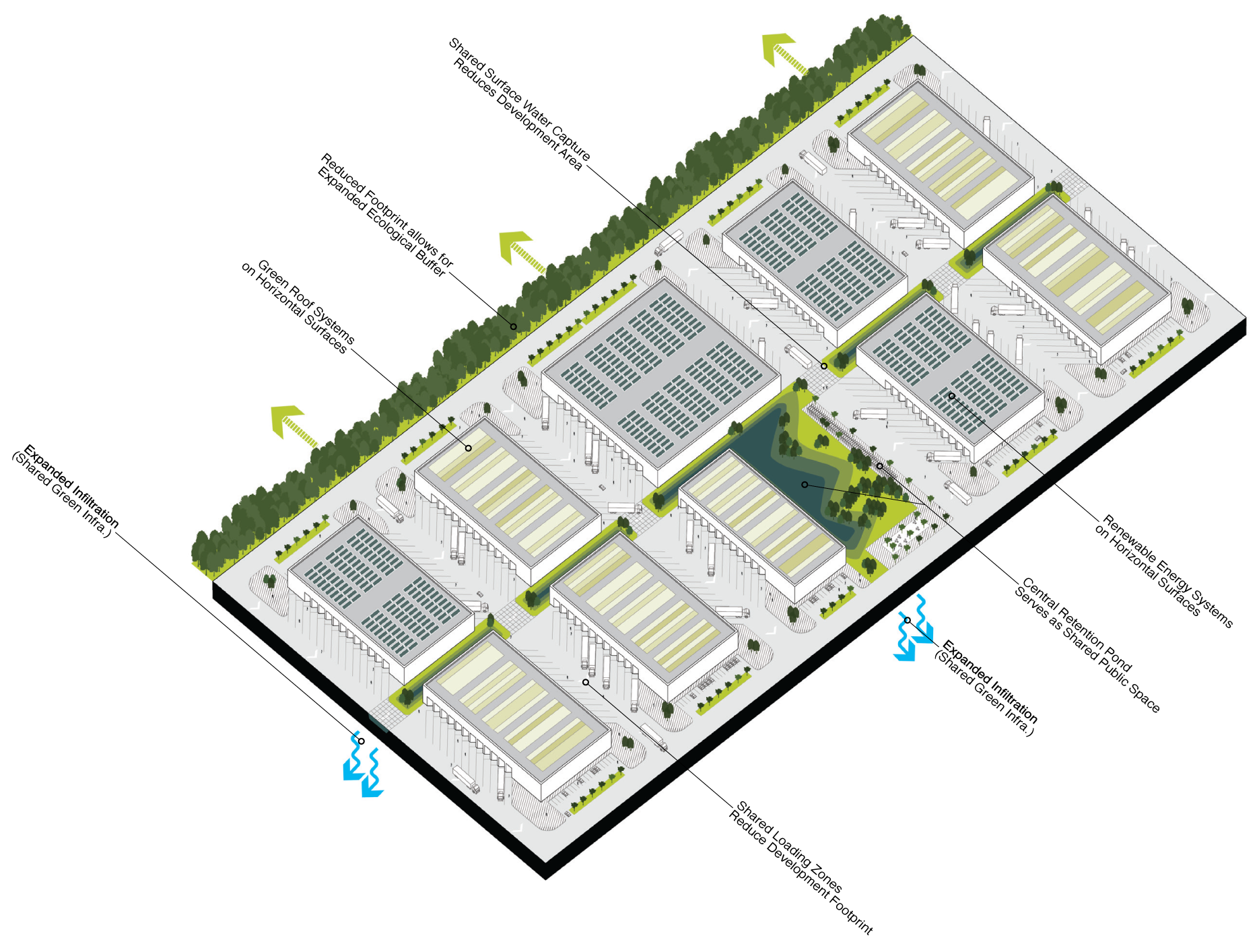

Most of the major concentrations of warehousing and distribution are within 10 miles of New York City, which is a reflection of the value of having these facilities close to ports, airports, and the large population in the core. These locational advantages should be protected, even as new technologies make these sprawling facilities more compact and responsive to environmental priorities in places like the Meadowlands.

Finally, lands currently used for energy production should be evaluated in consideration of long-term changes in energy production and transmission. Waste-management facilities should be equitably distributed across the city and upgraded or adapted with technologies that reduce noise, odor, and other externalities.

Almost half of the region’s industrial jobs are in commercial and mixed-use areas around downtowns and centers outside of the urban core—places like Trenton, Poughkeepsie, and New Haven—that have a strong industrial legacy. These industrial districts share some of the same issues and opportunities as those in the region’s core, although at a very different scale and under less displacement pressure.

Yet they also have the potential to anchor much of the region’s future economic growth, and to accommodate new homes that will help relieve the region’s housing shortage. Developing balanced growth strategies that attract new businesses and population while improving opportunities and quality of life for existing residents is a major challenge. Retaining and growing manufacturing and distribution jobs, and giving residents the skills to advance their careers in these sectors, should be key elements of these strategies.

Future use for production-related activities should be based on access to existing labor and skill sets, as well as the capacity to link to other institutional partners. Many of the strategies are the same as those described for the urban core: allow new mixed-use building types, connect the sites to the rest of the downtown, and create guidelines designed to manage the transitions in scale and use at the edge.

Places of production in suburban areas include industrial parks and manufacturing “campuses” such as those found in the corridor of pharmaceutical industries in Somerset County, NJ, and the Hauppauge Industrial Park in Suffolk County. Many of these places are attractive to businesses looking for less-expensive office space, and therefore have low vacancies. However, many do not have the digital infrastructure and services needed by an increasing number of companies, and also lack the transportation, amenities, and mixed-use character sought by many high-value industries.

In evaluating these places for possible investment, priority should be given to local employment impacts, the capacity of the facility to adapt to changing industry trends, and the ease of connection to local neighborhoods and open spaces. Regulations must encourage mixed-use development and flexible adaptation of the typical one-story industrial shed to create more flexible space, such as carving into and clipping onto it as demonstrated at the Bayer facility in Berkeley, California.

Some industrial areas are in less-developed parts of the region, such as between the New Jersey Highlands and the first ring of suburban communities. Sometimes, these sites encroach on natural open spaces—and would encroach on the tri-state trail network proposed in this plan. But large industrial sites, particularly those that are underused, should be reintegrated into nature.

Several larger-scale industrial landscapes, such as major landfills and large-scale fuel-storage facilities, need district-wide plans that address their scale and complexity. This scale makes it possible to explore innovative models for industrial landscape design. These are places, such as the Meadowlands in New Jersey, where large-scale natural systems and large-scale infrastructure systems intersect, requiring a more comprehensive approach that addresses environmental and land-use issues. The cost of environmental remediation, the potential contribution to the larger open-space system, and the impact on resilience to sea-level rise, storm surges, and other effects of climate change should be considered along with the economic benefits of maintaining industrial functions. Examples of places that are attempting to balance these objectives include Freshkills Park on Staten Island, the Menomonee Valley redevelopment project in Milwaukee, and Emscher Park in Germany.

Most industrial zoning relies on outdated and oversimplified definitions of manufacturing. Cities that are known for proactive and progressive efforts to grow their manufacturing economies, such as Portland, OR, and Berkeley, CA, manage the complexity of urban production in several ways. The lists of defined uses are extremely detailed and are updated on a regular basis. The scale of the zoning districts is small, enabling the regulations to be calibrated to particular conditions. The review process enables a certain amount of discretionary review based on how the use performs in terms of impacts such as noise, dust, odor, and the role of that use in the overall economy of the district. As sensors measuring noise and other pollution become more affordable, data-driven approaches can support more flexible zoning models that allow for mixed-use manufacturing.

State funding for environmental remediation needs to support a more comprehensive approach that links remediation to overall objectives for health, open space, and job creation. The overall environmental process should be reformed to combine environmental review with comprehensive planning, and to expedite redevelopment of land for specific uses and aid in the reclamation of industrial sites and buildings.

Production is for the most part locally based, and depends on the specific resources, geography, labor force skills, and industrial legacy of the specific place. But federal industrial policy largely focuses on integration and the uptake—most commonly by multinational firms—of cutting-edge technologies, as well as on commercialization and productivity increases. While there are a few national initiatives aimed at being more place-based, such as the Investing in Manufacturing Communities Partnership, these do not receive sufficient funding. Realignment of federal policy would mean place-based, mission-driven organizations would be recipients of federal funding, and other support programs would be more narrowly calibrated to the local production ecology.

Implementation of these actions would allow the region to balance the need for industrial space and industrial jobs with the demand for more housing, open spaces, commercial development, and climate adaptation. There would be no net loss of industrial space in the region’s core, although much of the existing space would be converted to more flexible, mixed-use activity. Both New York City and the region’s other downtowns would retain a vital production sector that successfully co-exists with residential neighborhoods and service industries. The region as a whole would retain a million industrial jobs, and high-value sectors would likely grow. More residents without college degrees would be able to pursue successful, living-wage careers. The reliability of the transportation and energy systems would be maintained at a reasonable cost, because there would be sufficient space available at the right locations. And fewer communities would be burdened with environmental hazards from outmoded or abandoned industrial properties.

Of all these actions, the highest cost will be for brownfield remediation, with state programs and tax credits providing the largest source of public funding to expedite cleanups. Brownfield remediation costs vary widely, from several hundred thousand dollars for a straightforward gas station cleanup to multi-million-dollar cleanups for large facilities. But a federal study found that each dollar of brownfield funding leveraged $18 of economic benefit. Studies of New York City and state programs have found comparable benefits. Infrastructure upgrades would require a combination of state and local funding, depending on the site and objective. Workforce-development funds could come from a variety of federal, state, and local sources, and could leverage private-sector training resources.

Most of these infrastructure and cleanup expenditures would be needed for any type of redevelopment of industrial properties. Still, the long-term benefits of job creation, tax revenues, and health and environmental improvements are substantial. There would, however, be some trade-offs from forgoing residential and office values, which would pay higher land prices and taxes on some industrial land, that need to be weighed against the benefits of better-functioning infrastructure and a more balanced economy.

1. RPA, “Charting a New Course,” 2016