Riding in a bus or streetcar on a city street is as important as riding beneath that same street on a train, but receives far less public attention. Infrequent availability and slow speeds have led to falling bus and streetcar ridership. But with the right combination of smart technology, greater availability, faster travel times, and new lines, riding a bus or streetcar would no longer be the last and least desirable option in the region’s transit system—it may even be the first.

In the urban center, low-density suburbs, and everywhere in between, buses and light rail lines must be actively managed to remain competitive with other ways of getting around.

There are a number of opportunities for improving how New Yorkers get around, without having to build any new tunnels.

The Triboro line would run for 24 miles from Co-op City and/or 149th Street and Third Avenue in the Bronx to Bay Ridge in Brooklyn, providing new passenger rail service on an existing, underused freight right-of-way. As a circumferential line, the Triboro would intersect with 17 subway lines and four commuter rail lines along its route. It would provide better north-south transit service between Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx—a need that is growing as job growth accelerates in the boroughs (more than 50 percent of New York’s job growth in the last 15 years has occurred outside Manhattan).

The Triboro line would increase connectivity between the boroughs and to Manhattan-bound subway lines. It would increase reverse-commute access to the suburbs for residents of the boroughs through outbound Metro-North and Long Island Rail Road services.

Triboro could be built faster and more cheaply than other recent, large-scale transit projects in the New York region because most of its right-of-way already exists.

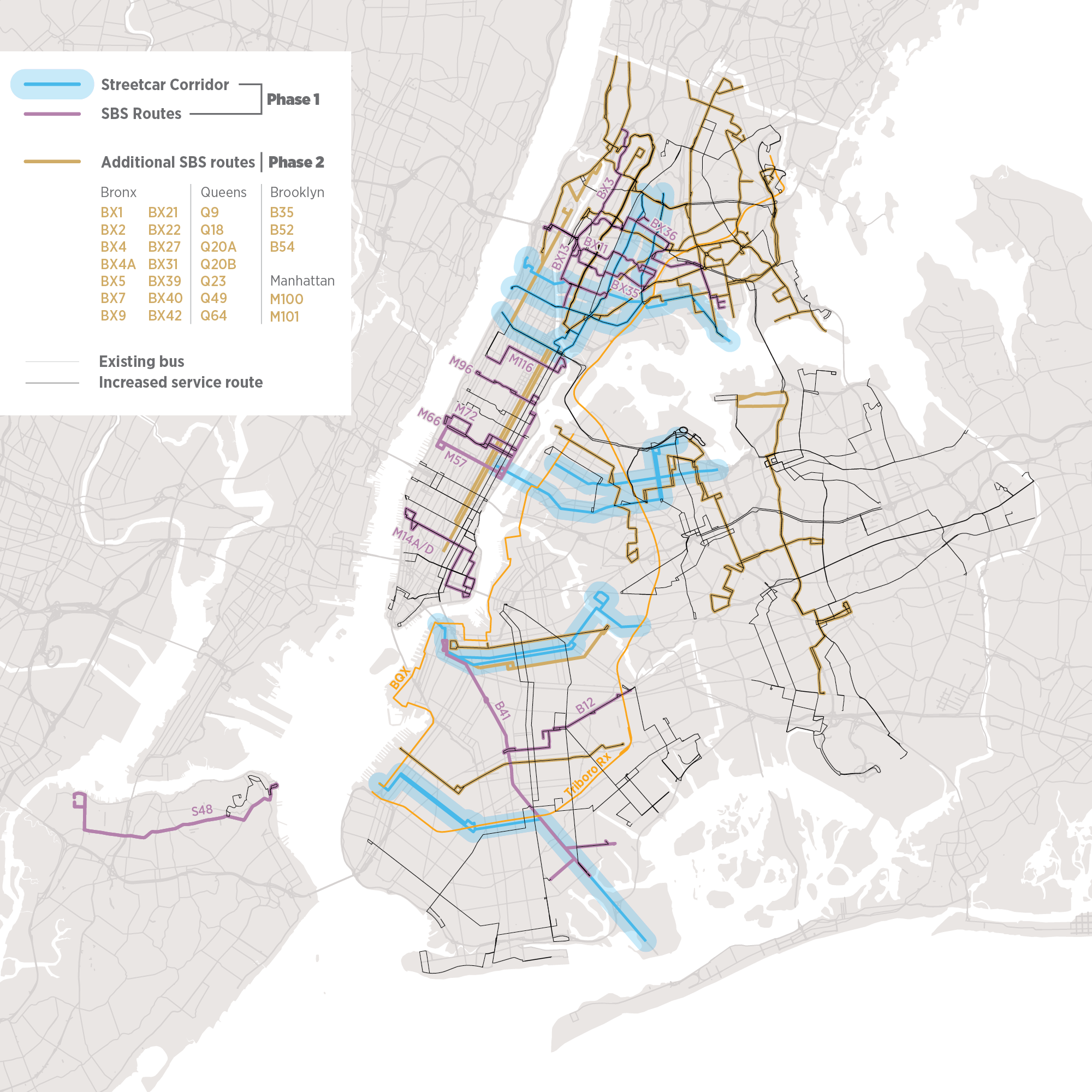

NYC DOT’s Select Bus Service (SBS) doesn’t have all the features of Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), but it does offer off-vehicle fare collection and a combination of preferential lanes for buses, queue jumping traffic signals, and longer station spacing. NYCDOT should add 15 more routes to the program. The bus lines with the highest use and the slowest speeds should be converted to SBS to improve transit service in Lefferts Garden, Ridgewood, Mott Haven, Riverdale, Soundview, and Jackson Heights, among others. Savings from SBS lines’ greater efficiency and lower operating costs should be dedicated to increasing their availability and improving access to the subway system. Many other bus lines could also be simplified and redesigned for faster service.

A proposal to build a light-rail line along the Brooklyn and Queens waterfront, a project known as BQX, has kicked off a lively public debate about reviving rail lines in New York, as many cities around the world have done in the last decade.

Surface rail can operate faster and be more flexible than buses on narrow streets, and can—and in most cases, should—trigger new development near stations. Eight streetcar routes should be considered in Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. Depending on how well these projects progress, 22 more routes should be considered for either streetcars or SBS.

The MTA and other surface transit providers should accelerate the adoption of contactless fare collection to allow riders to tap in their fare as they step onto the bus, eliminating delays caused by passengers paying in cash or dipping their magnetic fare card as they do today. Although transitioning to contactless fares will be complicated and expensive, it will cost less than installing off-vehicle fare collection at kiosks along all routes and all stops, including more than 16,000 bus stops in New York City alone. As an added bonus, the same contactless card could be used universally on all transit systems across the region.

Outside New York City, many bus routes struggle with low ridership and high per-passenger costs, while others serve their communities well and have the potential to provide better service with more investment.

A comprehensive analysis of six suburban bus systems identified:

To support population and employment growth in New York City and the region’s other cities, public transportation providers should introduce new service or improve existing service along certain corridors. Of particular interest are corridors that:

Connecticut’s new Fastrak service—a bus rapid-transit system between Hartford and New Britain—is proof that providing dedicated lanes for bus service can dramatically cut travel times, improve reliability, and increase ridership. There are three other corridors in the region that should make similar investments in either light rail or Bus Rapid Transit.

For each of these corridors to succeed, they must be developed along with the creation of more compact and walkable transit-friendly communities. Stations along these corridors should be optimized for drop-offs as on-demand and autonomous vehicles gain in popularity, providing critical “last-mile” access to the corridor from less-dense suburban communities.

Passaic/Essex Corridor: Paterson to Newark

The Passaic/Essex corridor spans a distance of 14 miles from the city of Paterson to downtown Newark, New Jersey’s second largest city. Restoring service on this line—the former Newark Branch of the Erie Railroad—would be transformative for Paterson, as well as for Clifton, Nutley, and Belleville. To maintain compatibility with existing freight service on part of the line, the new passenger service should be light rail (instead of BRT). Many of the nine train stations have been torn down, but their original sites should be evaluated for future stops.

The Interstate 287 Corridor

The Interstate 287 corridor extends for 30 miles, from Suffern in Rockland County, over the Mario Cuomo (Tappan Zee) Bridge, to Port Chester in Westchester. There is excellent Metro-North rail service to New York from the three Westchester communities of Tarrytown, White Plains, and Port Chester. But east-west transit service—both to feed the Metro-North line and for local travel within and between Westchester and Rockland—is slow, unreliable, and hampered by congested roads.

Exclusive lanes for buses and three-or-more-occupant carpools should be implemented on I-287 from West Nyack to the Tappan Zee Bridge, and then from Tarrytown to White Plains. This would involve a combination of new right-of-way using surplus land along I-287 and rededicating lanes, either permanently or for certain times each day. The lanes would have direct busway tie-ins to the rail stations in each of the three Westchester cities, and would offer more local bus services.

Nassau Corridor: Oyster Bay to West Hempstead

The Nassau Corridor spans from Valley Stream on its southern end to the Oyster Bay at the north, a total of 22 miles in length. Two lightly used LIRR lines with low usage could be converted to light rail or BRT—either of which would provide more frequent service and lower operating costs. More frequent service could also help to establish a new north-south transit alternative, and both better serve existing land uses and jumpstart new development along the line.

Implementing all of these bus, streetcar, and light rail improvements could lower transit times for as many as a billion rides per year. Faster and more reliable service, shorter wait times, and more convenient and comprehensive service would reverse the decline in bus ridership such that the number of riders would grow faster than the population. Reliable service could reduce the growth of transportation network companies for surface-transit trips and mitigate rising congestion on New York City streets.

Better bus service can also be cost effective, as the expense of additional service could be partially offset by higher bus speeds that shorten route times. And routes that are to be reinforced should be selected in part because of their high ridership potential, which would result in a relatively low cost per rider. New BRT, streetcar, and light rail lines can employ tax-increment financing and other forms of capturing a reasonable portion of increased real estate values to pay for improvements.

1. RPA, “Surface Transit: Upgrading local mobility for the region,” 2017