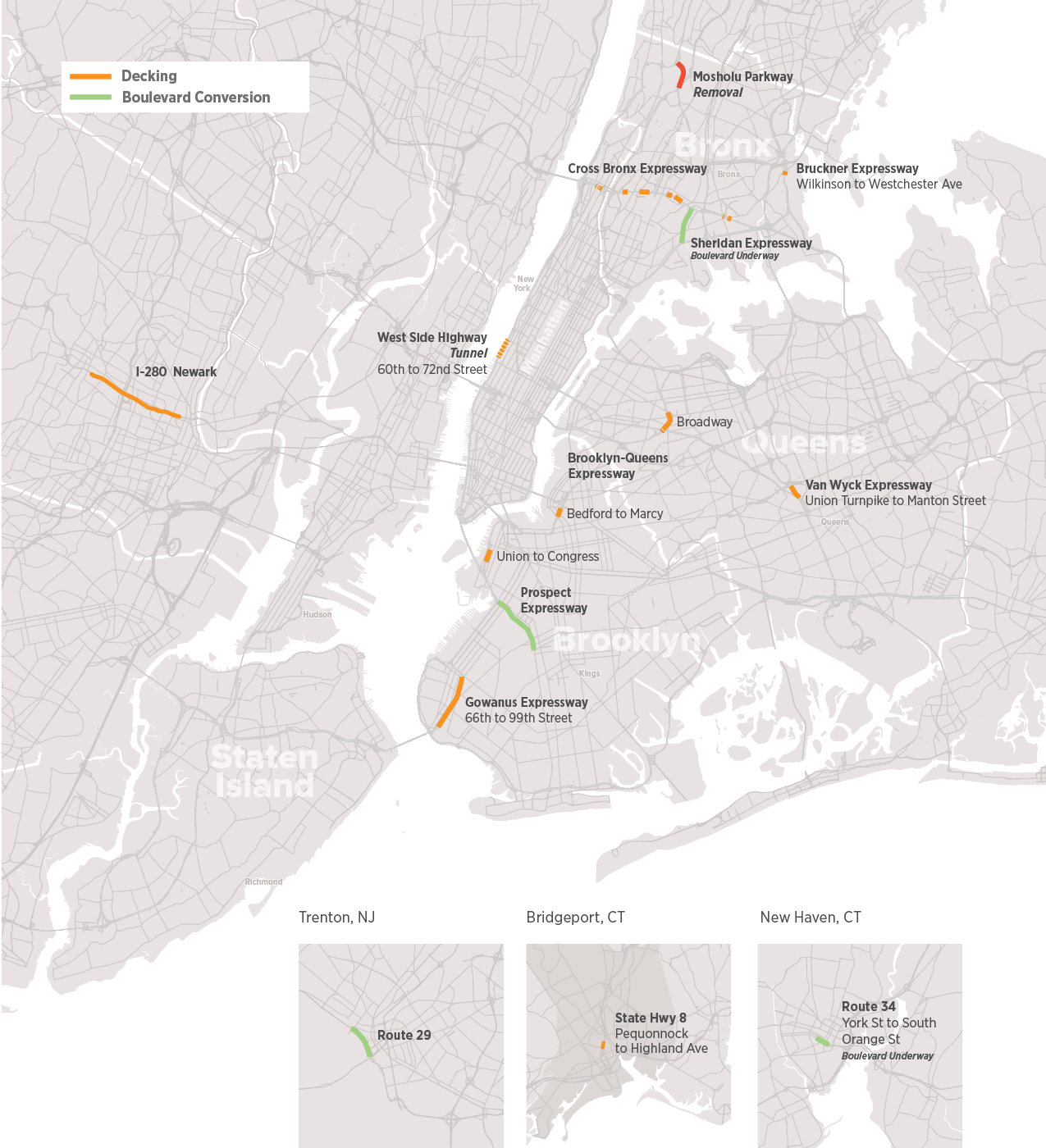

Whether the roadways were sunk in trenches, elevated above, or built at grade, they broke up neighborhoods, resulted in dangerous and noisy streets, and led to high rates of asthma and traffic accidents. The most problematic examples include the Cross Bronx Expressway, Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, and Sheridan Expressway in New York; Interstates 280 and 78 in New Jersey; and Route 34 and I-95 in Connecticut.

In other cases, highways were built at the water’s edge or in parks, mainly because that land was already publicly owned and planners at the time wanted to create parkways. Roads that cut off access to rivers and park space include the Belt, Henry Hudson Parkway, and Hutchinson River Parkway, FDR Drive, and Sheridan Expressway in New York; Routes 21 and 29 in New Jersey; and Routes 8 and 34 in Connecticut.

State DOTs should work with communities to transform urban highways and repair the harms of the past

Route 34 in New Haven is being turned into a boulevard, reducing the roadway’s width and adding pedestrian amenities and new development.

Other opportunities to boulevard existing highways include:

- The Prospect Expressway in Brooklyn: From Third to Church avenues, a distance of almost two miles, it should be narrowed to one lane in each direction, opening up land for a new bicycle “highway,” residential development, and public spaces.

- Route 29 in Trenton: A project that has been discussed for decades, it would convert a mile-long stretch of limited-access highway between Trenton’s downtown and riverfront. Tying the road back into the city grid and adding pedestrian features would have tremendous social and environmental benefits.

Outcomes

These actions would stitch together neighborhoods, restore communities, and improve local mobility. They would create over 100 acres of reclaimed land for development of housing, mixed uses, or open spaces. Removing, burying, and decking over the region’s highways will improve the health of communities by mitigating some of the noxious air and noise impacts. It would also reconnect parks and other open spaces for recreational purposes such as walking and biking options.

Paying for It

The cost of these interventions would be significant, and funding would need to be prioritized within state and city transportation budgets. For example, the New Haven Route 34/Downtown Crossing will cost an estimated $74 million, while some of the more extensive projects will cost far more. Many of the benefits, however, can be monetized in a short time period, including selling off parcels of land for redevelopment, which would add valuable real estate to the tax rolls. Other benefits have longer pay-back periods, such as better public health outcomes and cities with more development and a higher tax base.