In a dense region like ours, the demand for street and road space will always outpace the supply. The allocation of space leaves too little room for walking, biking, and transit, largely the result of decisions made throughout the 20th century. Progress has been made: New York City’s efforts to make streets safer has succeeded in cutting the number of annual traffic fatalities nearly in half, from 400 in 2000 to 229 in 2016. New York City has also built 1,200 miles of bicycle lanes, dozens on public plazas, and 15 Select Bus Service routes with more planned by 2030. One of the city’s jewels, Prospect Park, has recently been closed to cars. Jersey City introduced bike-share services in the last year, and White Plains has plans to improve bike and pedestrian infrastructure.

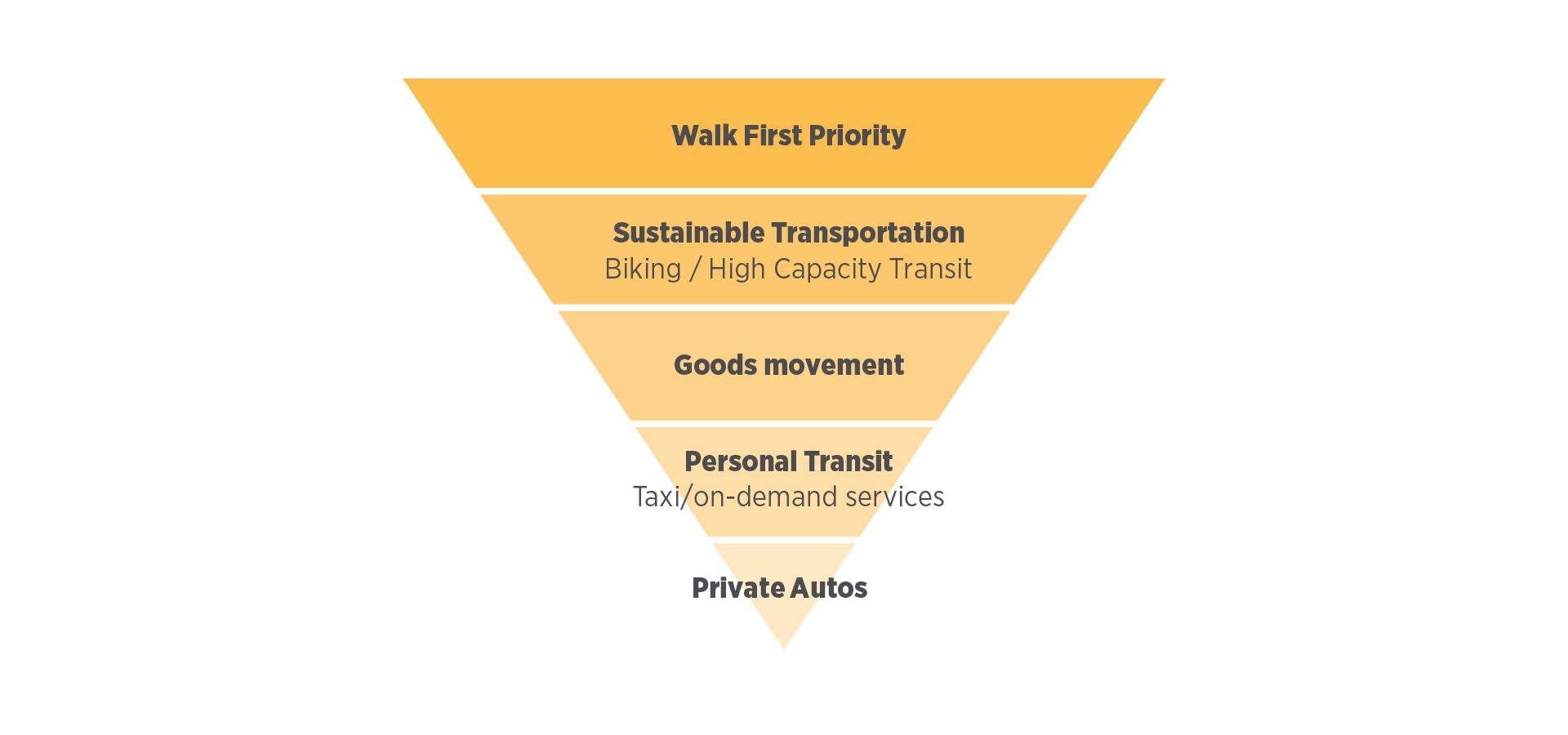

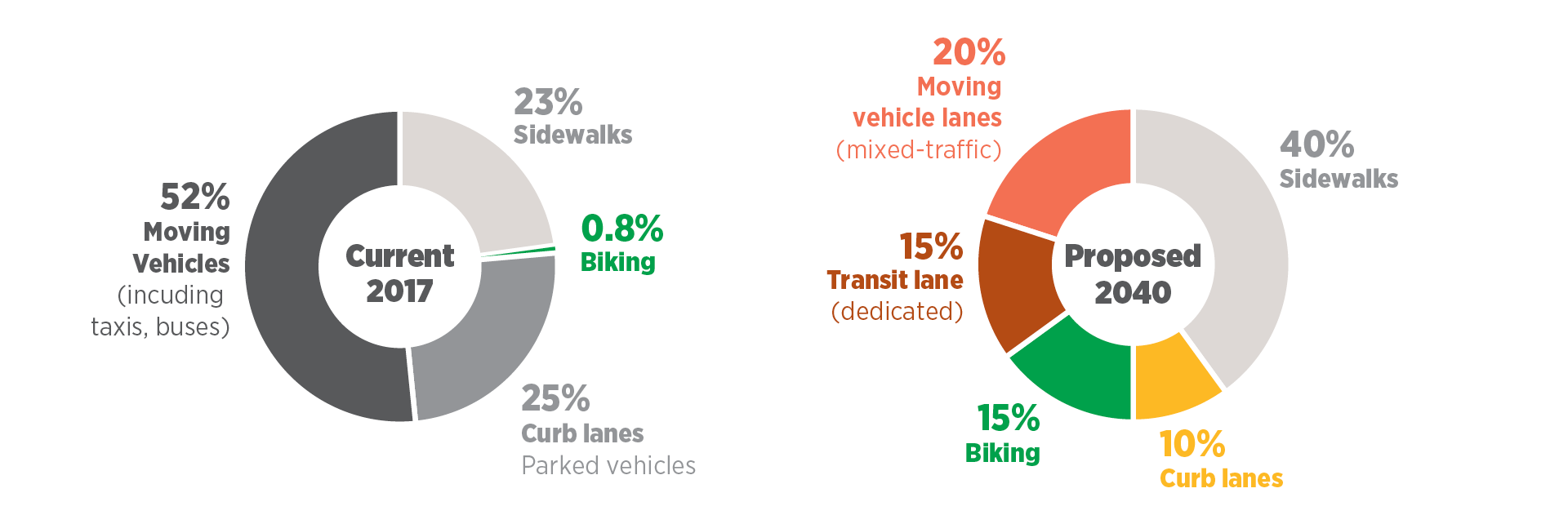

But too many of our streets are still unsafe and given over to automobiles. Less than a quarter of all New York City’s street space is dedicated to sustainable modes of transportation—walking, cycling, and exclusive bike lanes—and most of this is concentrated in Manhattan and denser parts of the city. The vast majority of our streets and roads are handed over to private automobiles, taxis, and transportation-network companies’ delivery vehicles, freight trucks, construction equipment, garbage trucks, buses, and emergency vehicles. Many of these vehicles serve vital purposes, but they also cause air and noise pollution, clog up streets and roads, cause crashes, and generally increase the stress levels of drivers and pedestrians alike.

By not managing roads effectively, valuable space isn’t used efficiently. Buses with dozens of passengers are stuck in the same traffic as vehicles with one passenger. Delivery and garbage trucks are free to make their runs at any time of day—even the busiest times. Clean, electric vehicles aren’t given any preference over vehicles that burn gasoline and cause air pollution. It costs more to take the bus or the subway into Manhattan than to drive over four of the East River Bridges. Car owners are provided free or heavily subsidized parking even though that land could be used for other purposes. And too little has been done—particularly outside New York City—to make streets safe.

We must rationalize how we use our streets and roads. Not only is it vital for public health and quality of life, but also critical to the region’s economic vitality.

Proactive management and better design will make it easier to get around and create better, healthier neighborhoods

Use technology to manage traffic throughout the day

Just as technology is multiplying the number of ways people can get around—with on-demand, shared, and ultimately autonomous vehicles—technology can also multiply the number of ways cities can manage traffic.

Digital signage could notify people when streets are temporarily closed to traffic. Technology already allows drivers to navigate the city through apps that report traffic crashes, speed traps, and street closures in real time. “Geofencing” technology could even more proactively redirect drivers to avoid particular streets during peak travel periods or districts prioritized for pedestrians and cyclists during weekends.

To integrate technology into street management, cities should:

- Improve driver awareness of policies with temporal information on streets and curbs, reducing confusion and improving compliance. This would require revising future street geodata (e.g., NYC’s LION dataset) to include information on timesharing and time-based curbside restrictions, if/when applicable

- Use image analytics and license-plate recognition to support real-time parking information and enforcement

- Introduce digital wayfinding signage, particularly for shared spaces, expanding on existing technologies like LinkNYC and MTA’s On the Go kiosks

- Anticipate the need for future wayside digital technology with expanded sidewalks and curb bulbs at intersections

Green the streets, improve health, and strengthen the urban ecosystem

There are many reasons to green the streets. More trees and landscaping make for a more pleasant streetscape, giving people places to sit and relax. They help clean the air, reduce heat, and absorb noise. They also absorb rainwater, and reduce storm-water runoff and flooding from heavy rains, especially in low-lying areas. New York and other communities should build on successful initiatives to improve the urban ecosystem—and boost public health—with bioswales, street trees, landscaping, and permeable pavement.

Promote efficient, environmentally-friendly solutions to lower truck traffic for goods distribution

A functioning economy requires not just the movement of people, but also goods. Millions of shipments get delivered by truck every day—a number that could grow exponentially with e-commerce. Although New York City does not have a consistent or strategic delivery-management system, it is starting to address this through a new urban freight plan. Deliveries would cause less traffic if cities implemented the following measures:

- Designate more truck parking and loading areas, even if it requires eliminating on-street parking

- Repurpose curb space for wider sidewalks and loading zones

- Use textured pavement to delineate and designate areas for deliveries on shared streets.

- Provide incentives for off-hour deliveries, pedestrian deliveries, and deliveries with non-motorized vehicles

- Adopt low-emission zones in dense urban areas that ban or restrict high-pollution vehicles

- Enforce anti-idling programs, and transition truck fleets to electric and alternative-fuel vehicles

Adopt single-stream recycling and other waste-management measures to reduce traffic and sidewalk crowding

Waste and waste pick-up have a big impact on our streets. Trash bags are strewn along already narrow sidewalks, attracting rats and giving off foul smells in the summer heat. Hundreds of sanitation trucks are deployed every day—some for commercial waste and recycling, others for residential waste and recycling. They crowd city streets, slowing traffic and fouling the air. And recycling rates are still very low.

A unified, single-stream recycling system should be adopted for both commercial and residential waste in New York City. In a single-stream system, all recyclable waste is collected by the same trucks, to be sorted into different streams—paper, metals, plastic, etc.—by special facilities. Single-stream systems have been adopted in thousands of municipalities across the U.S., and despite more upfront capital costs, they dramatically reduce the number of sanitation trucks on the road, boost recycling rates, and cut back on the amount of trash trucked to landfills.

Other waste-management measures should be taken to reduce traffic and sidewalk crowding, including:

- Rationalize and consolidate private commercial-waste collection

- Require trash bags to be placed in reusable bins, such as recessed bins at the curbside, instead of loose on the sidewalk

- Explore shared municipal binning, instead of curbside pickups at individual homes

- Explore requiring pneumatic waste-collection systems in all large, new-housing and commercial developments

Democratize planning for small-scale changes to local streets so government can focus on broader citywide challenges

The New York City Department of Transportation oversees one of the most complicated urban transportation networks in the world. Managing 6,000 miles of streets and highways, nearly 13,000 signalized intersections, 800 bridges and tunnels, and many other infrastructure elements is a massive undertaking, and means the DOT cannot be involved at the hyper-local level. But communities could be empowered to make targeted decisions about their local streets.

San Francisco, for example, recently launched GroundPlay, a multiagency effort to empower local leaders to make community-driven changes in their neighborhoods. GroundPlay identifies specific criteria for projects up-front, and then devolves some planning and design responsibility so citizens can work with their neighbors on public street art, plazas, and certain pedestrian safety projects.

New York City should consolidate the myriad of application-based processes that different city agencies already run into one well-branded and unified entity. Empowering communities to take ownership of their streets would foster a culture of planning and vibrant street management.

Outcomes

Paying for it

Many of the actions—redesigning the physical streetscape, implementing new technologies, putting in new bike and transit lanes and plazas—come at a substantial cost. An appropriate revenue source would be a share of congestion charges for entering the central business district or higher municipal parking curb-use fees that would also limit car use. Other actions would have a low monetary cost, such as regulations to limit car or truck use, but require a workable political consensus that is often difficult to achieve. Both short- and long-term success would depend on maintaining momentum from recent successes and replicating those successes in more locations and cities, effectively demonstrating benefits of more transformative change, and enlisting local organizations and business improvement districts to design district or neighborhood solutions.