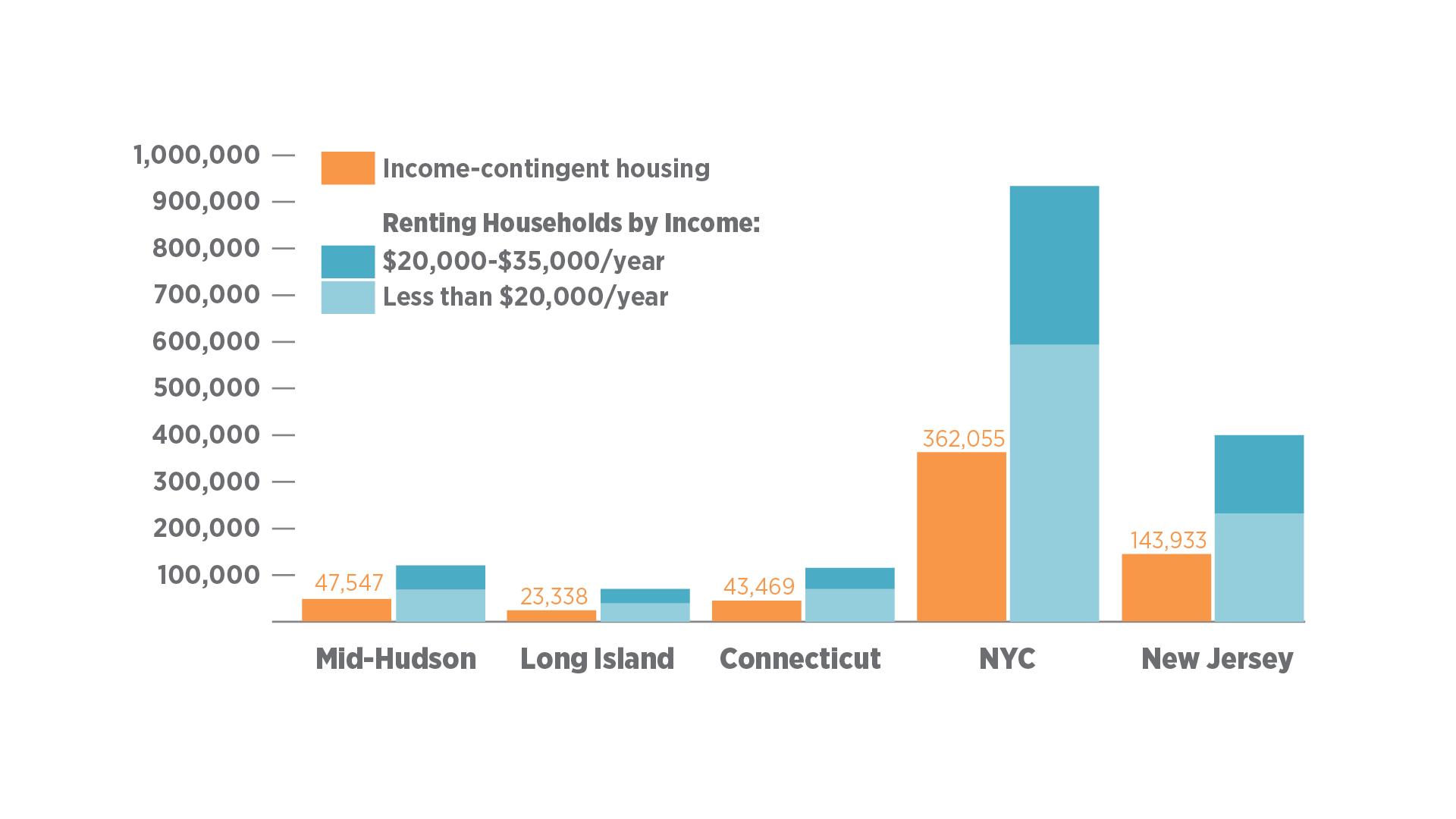

The key to creating enough affordable housing to sustain a broad middle-class is to build enough homes to create a rational housing market, although the main housing needs of the region are at the extremely low income levels, for whom the market alone has no history and no expectation of providing affordable housing. There are over a million renting households in the region making under $20,000 a year—an income too low not only to find housing on the open market, but also to be eligible for government workforce housing programs like the Low Income Housing Tax Credit. But there are only about 670,000 apartments that are part of programs where tenants are guaranteed to pay only what they can afford, and can be expected to be affordable to very low-income households, such as Public Housing, Housing Choice Vouchers, and HUD 202 Senior Housing.

There is, however, a robust government sector dedicated to subsidizing new and existing homes. In New York City, there has been an explicit municipal commitment to building 5,000 to 8,000 government-subsidized homes every year for nearly three decades, and almost all new rental housing has used tax exemptions as a partial financing tool. Elsewhere in the region, tax-exempt bonds and low-income housing and historic tax credits account for a significant amount of new housing—up to 40 percent of all construction in some counties. Even more money is spent to preserve affordable homes, provide emergency shelter for the homeless, and support low-income people with housing subsidies through public housing or vouchers. Because so many homes require large subsidies, this government-sponsored housing is a de facto part of our housing market.

While additional funding is needed, particularly from the federal government, existing subsidies can be used far more effectively than they are today.

Subsidies should target housing that cannot be produced by the private market

Government money should be used to create the type of housing not created by the market instead of for uses the market can or should do unsubsidized. This includes all types of subsidy, whether it comes from tax exemptions, capital dollars, or other sources. Every form of subsidy should be more fair and transparent, and support greater efficiency in both the public and private sectors.

Move subsidies toward preventing homelessness and housing the lowest-income New Yorkers

Capital dollars should be channeled toward low-income rental subsidies, housing-court help, senior and supportive housing, and permanently affordable housing for people who have the least amount of market choice. Rental subsidies have consistently been shown to be the most effective means of housing low-income households and preventing homelessness. Construction overall should be stimulated by loosening the zoning envelope and allowing for more development opportunities, not by using government subsidy to attempt to outbid the private market for a constrained amount of housing construction opportunities. Numeric goals for building and preserving affordable housing units should be ended in favor of a qualitative, not quantitative, approach that focuses on reducing overall rent burdens and housing expenses across the board. A health impact assessment on housing subsidies could help identify the highest priority investments.

Put all subsidies through a competitive process

The most efficient housing subsidies, such as 9 percent tax credits, are put through a competitive process for a limited pool of money. However, most tax subsidies and some capital subsidies are as-of-right, with no ability to funnel money to the most deserving projects, and in the case of tax exemptions, no ability to ultimately cap the cost of the subsidy. Bidding on subsidies would both provide budget stability for states and municipalities, and ensure government dollars are used most efficiently. This could also be expanded to tax subsidies for economic-development projects.

Target middle-income housing programs to home ownership, not rental housing

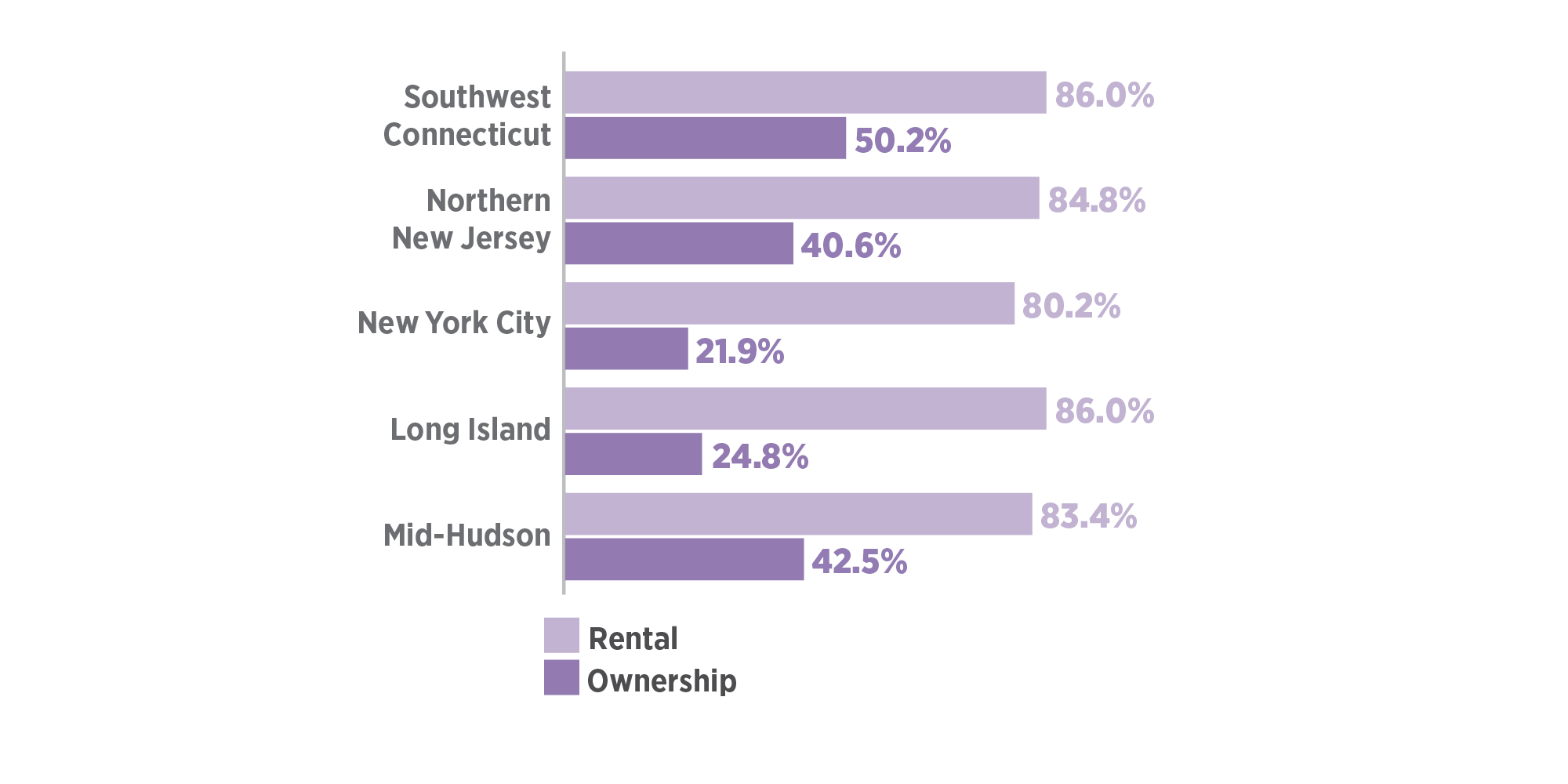

Although subsidies should be targeted at those most in need, there are cases when it may make sense to spend a limited about of money to incentivize middle-income housing as well. The lack of supply at middle-income ranges is, however, for home ownership, not rental housing, and incentives should be targeted accordingly. Not having middle-income homeownership also leads middle-income households into entering the rental market, where they are often able to outbid lower-income households for the available rental housing, therefore reducing the affordable rental stock. And in areas needing revitalization, the stability provided by homeownership is of more value in this effort, as is the likelihood these programs will attract middle-income buyers.

Treat publicly owned land as an asset, not a liability

Instead of selling land to developers, municipalities and states should treat public land as a significant and non-replaceable public asset. The government should retain ownership, either directly or through mechanisms such as community land trusts, mutual housing associations, or other entities. This would still allow municipalities to lease the land to developers to build affordable housing or for economic development projects. In addition, steady lease payments, as opposed to fluctuating property taxes, would help bring stability to the underwriting and financing of development.

Use government programs to create more competition in the housing industry and jump-start new technologies

Many of the recent innovations in construction technology in the New York region—such as multifamily modular housing and passive housing technology, which uses construction techniques to reduce heating and cooling needs and greatly reduce energy costs—have taken root largely because government programs have either directly or indirectly encouraged their initial development. Government also has the ability to give an edge to smaller businesses and industry sectors, such as minority- and women-owned businesses and the nonprofit sectors, which can provide more competition in the industry and bring down housing costs overall. Whenever possible, government subsidies should give preferences to these sectors and provide requirements and incentives to use new technologies that can bring down the cost of construction.

Consolidate marketing and make tenanting fairer

Most cities around the world with significant amounts of government sponsored or social housing have an easy and rational system for obtaining this housing, rather than a series of lotteries and individualized waiting lists, each with their own process and requirements. Every county and large municipality should move toward a single application system where all subsidized housing would be available on a waitlist basis, with a single government agency overseeing the process and developing a comprehensive inventory of social housing.

Outcomes

Paying for it

In the short term, reforming our housing subsidy system would not necessarily cost more or less than it does now, but would use existing funds more efficiently—although in order to be most effective it would need to be coupled with additional federal investments in housing. In the long term, reforming our housing subsidy system saves money through retaining control over land; allowing government to leverage better terms from any affordable housing renewal; providing more competition and lower building costs through government incentive programs; and ending uncapped subsidies that can cost unforeseen amounts.

Recommendations

-

46Protect low-income residents from displacement47Strengthen and enforce fair housing laws

-

48Remove barriers to transit-oriented and mixed-use development

-

49Increase housing supply without constructing new buildings

-

50Build affordable housing in all communities across the region51Make all housing healthy housing