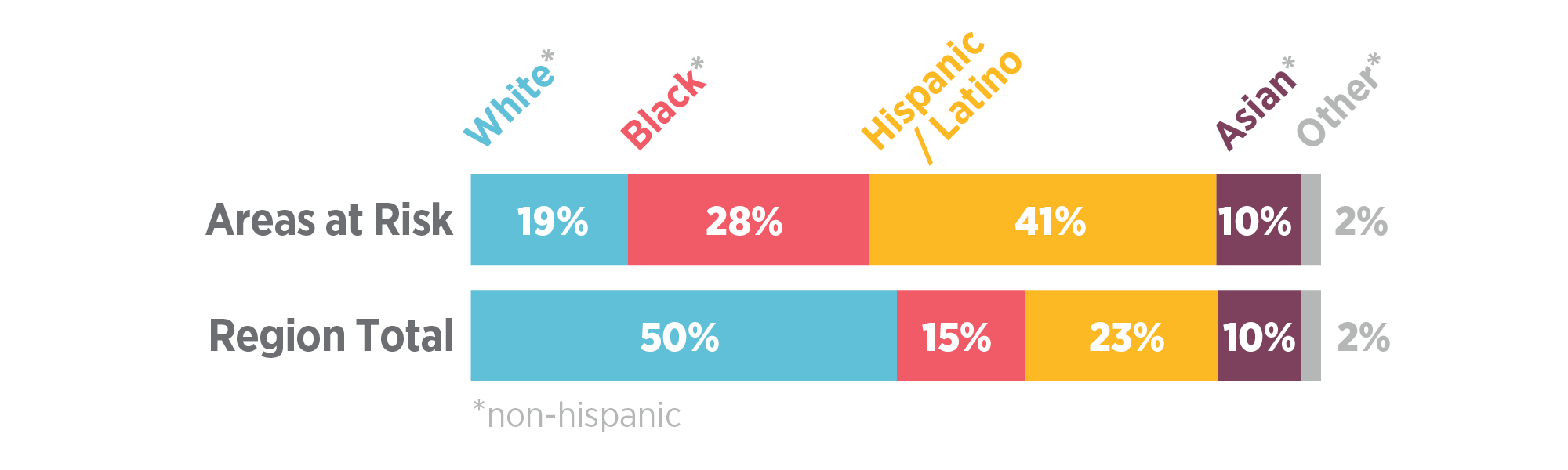

In the metropolitan region, more than one million low- to moderate-income households are vulnerable to displacement. Most at risk are residents of pedestrian-friendly urban communities with good access to jobs and services. As demand for homes in cities like New York, Jersey City, and Stamford push rents and sale prices upward, lower-income households are pushed outward. Even in cities with weaker housing markets—like Trenton and Newburgh—where many live in substandard or even unhealthy homes, new investment is sometimes resisted by residents who fear gentrification and eventual displacement.

To significantly reduce displacement and homelessness, the region needs to build community wealth, produce and protect more affordable homes, and strengthen tenant protections

New Jersey and New York are two of only four states in the U.S. where at least some localities are able to regulate and limit rent increases. While some jurisdictions—most notably New York City, through its rent stabilization system—take advantage of this, many do not: Only 38 municipalities in New York and 90 municipalities in New Jersey have some form of rent regulations. States should be more proactive in strengthening—or in the case of Connecticut, enabling—rent regulations at the municipal level to cover all municipalities where displacement is a concern. These should include some limits on the amount, frequency, and timing of rent increases. They should also allow for the right to a renewal lease, require minimum services for tenants, limit the grounds under which tenants can be evicted to nonpayment of rent or violation of an existing lease, and protect tenants from harassment, as New York City has done. At minimum, rental properties that receive any government subsidy should automatically be subject to rent regulations.

Strict enforcement of the housing maintenance code should accompany rent regulations in order to prevent landlords from displacing low-income tenants through lack of upkeep and proper maintenance. And when fines are not effective, municipalities should conduct the repairs proactively, with a foreclosable lien filed against the property. Funding for enforcement of the rent regulations and housing maintenance code is also critical.

Provide free legal counsel to those most at risk

Approximately 400,000 eviction actions take place each year southern New York State and central/northern New Jersey counties, with more than three-fourths in New York City and New Jersey’s Essex, Hudson, and Middlesex counties. Even when tenants win in court, legal fees and lost wages from attending court often create a downward financial spiral, leading to more financial struggle, evictions, and often, homelessness.

Cities and counties, with state support, should provide free legal counsel to all economically vulnerable residents facing eviction. The cost of providing counsel would be at least partly offset by future savings from preventing homelessness and associated shelter costs, and from not needing to replace affordable housing that may be lost when a tenant is evicted. Free legal counsel would also help to enforce anti-harassment policies, such as those passed in New York City in 2017, and prevent landlords from coercing tenants into leaving their home due to negligence or intimidation.

End homelessness

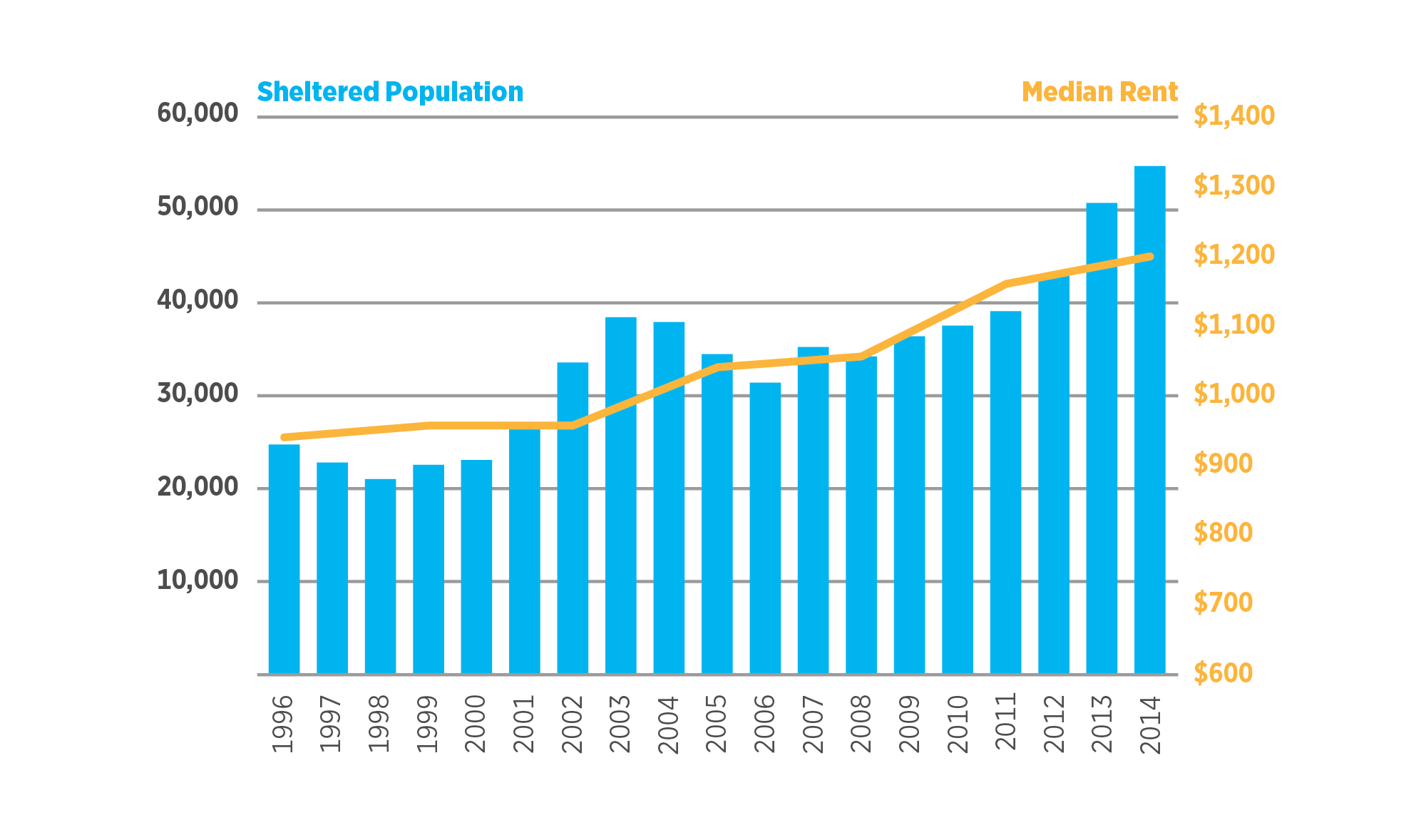

Homelessness in New York City has tripled over the last 20 years. On a per-capita basis, it trails only Washington D.C. and Boston among major U.S. cities. But other parts of the region have made great progress in reducing, or even ending, homelessness. In 2017, Bergen County, NJ, became the first in the nation to end chronic homelessness, and the state of Connecticut has the lowest number of people experiencing homelessness on record.

We can end homelessness in the region with the right level of commitment and funding. Although the magnitude of the problem in New York City makes it more challenging, the following strategies can apply to the entire region.

Both Bergen County and Connecticut run coordinated programs that are targeted at the community level. In Connecticut, the statewide Reaching Home Campaign includes representatives from the civic and public sectors focused on housing, health, education, job training, and food insecurity. By promoting the following policies, the campaign has significantly reduced homelessness throughout the state:

- Strengthening the state’s housing delivery system through the expansion of affordable and supportive housing

- Retooling the crisis-response system

- Improving economic security through income growth and employment

- Coordinating healthcare and housing stability

They agree on three core values, modeled after the federal Opening Doors plan to end homelessness.

- Homelessness is unacceptable because it is solvable and preventable.

- There are no “homeless people,” rather there are people who have lost their homes who deserve to be treated with dignity and respect.

- Homelessness is expensive for governments, and it is much more cost effective to invest in preventative and long-term solutions.

Invest in supportive housing

Supportive housing, which combines deeply affordable housing with individualized social services to help support resident health and well-being should be provided to individuals and families who are coping with mental illness, trauma/abuse, substance abuse, chronic illness including HIV/AIDS, or otherwise may need additional support. Supportive housing programs significantly reduce the need for emergency medical services, police, jails, homeless shelters, and other publicly funded services.

New York State has made progress on this front, building more than 50,000 units of supportive housing and recently committed to building another 35,000—but more is needed. All three states should expand or institute long-term agreements on funding and siting for supportive housing units, and should codify these into housing-agency budgets. Municipalities should adopt the “housing first” approach, which prioritizes providing people with permanent housing.

Outcomes

Paying for it

The actions with the highest direct public costs would be investments to maintain public housing and expand supportive housing. In New York City alone, the cost of returning the public housing stock to a state of good repair is estimated to be $17 billion, and the annual cost of managing and maintaining it at least $2.2 billion. Consistent with funding streams for other needed public infrastructure, federal funding should remain the largest source of revenue for public housing—and it is imperative that the region’s congressional representatives continue working to reverse the trend of declining federal support. States and cities will need to provide new revenue as well. New York City, for instance, is evaluating parking lots and other housing-authority property for mixed-use, mixed-income development that could both generate revenue to fix and maintain existing public housing and bring needed affordable housing, new jobs, and other services. The cost of expanded supportive housing would also be high, but would better serve this population while offsetting many other more expensive public services.

Creating permanent affordable housing on government land could be accomplished at a relatively low cost in places where local, county, or state governments own significant assets. But it would be higher in places where local governments and community organizations need to acquire public land, and where housing market demand is strong. The most cost-effective strategies should focus on neighborhoods where trusts can be established before prices escalate.

The cost of expanding rent regulation could range from very low (administrative costs of the expanded regulation plus enforcement) to moderate depending on structure (e.g., more expensive if additional subsidies are provided for new rent regulated apartments). Housing agencies will also need additional funding for enforcement. The main trade-off is rent regulation reduces turnover, making it more difficult to find an available apartment, and can subsidize higher-income residents; however, well-structured regulations can minimize these effects.

Free legal counsel could be fiscally neutral or positive when accounting for savings incurred from other government costs related to eviction, especially emergency shelter costs. In New York City, studies of the costs of providing free legal counsel for evictions have estimated municipal budget impacts from a $320 million surplus to a $203 million deficit.

1. RPA, “Pushed Out: Housing Displacement in an Unaffordable Region,” 2017

2. Glynn, Chris, and Fox, Emily, “Dynamics of homelessness in urban America,” 2017

3. Dwyer, Lee Allen, “Mapping Impact: An Analysis of the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative Land Trust,” 2015

4. Curbed New York, “De Blasio signs into law sweeping protections against tenant harassment,” 2017

5. City of New York, “Mayor de Blasio Signs Three New Laws Protecting Tenants From Harassment,” 2015

6. Coalition for the Homelessness, “Basic Facts About Homelessness: New York City,” 2017

7. Monarch Housing Associates, “New Jersey’s 2015 Point-In-Time Count of the Homeless,” 2015

8. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, “New York/New York III Supportive Housing Evaluation,” 2011

9. New York Magazine, “A Cash-strapped New York City Public Housing Authority Faces a Cut in Federal Funds,” 2017

10. New York City Housing Authority, “Report on the 2015 -2019 Operating and Capital Budget & the Fiscal 2015 Preliminary Mayor’s Management Report,” 2015

11. Stout Risius Ross, Inc., “Pro Bono and Legal Services Committee of the New York City Bar Association,” 2016