New rail connections link the Long Island Rail Road’s Oyster Bay and West Hempstead Branch Lines, and the once separated North Shore and South Shores are connected via a quieter rapid transit service that replaced noisy rail lines. Improved transportation and streetscapes enliven the new mixed-use downtowns along the route, while residential neighborhoods are quieter and safer for walkers and bikers.

This new connectivity and economic development supports what is now a true center for Nassau County, including a major office, research, entertainment and government hub from Mineola to West Hempstead. More people use shared, on-demand and autonomous vehicles, as well as shared parking and bikes, and the streets are safer and more pedestrian friendly. Previously segregated areas on Long Island are now a collection of neighborhoods with high quality, affordable housing and schools available for everyone, regardless of race, age or income.

In the first part of the 21st century Long Island was a typical American suburb, dependent on cars using congested highways to commute. At the geographical center of Nassau County, the Village of Hempstead, was a significant employment center and directly north of Hempstead, downtown Garden City was the center of Nassau County’s government offices and courthouses.

Both of these business districts were heavily car-oriented and lacked good transit connections, and surface parking accounting for almost a quarter of these downtowns, including public streets. Another area, the Roosevelt-Mitchell Fields east of Hempstead (known as the Nassau Hub) with universities, museums, and the Nassau Coliseum, also could not reach its full potential due to poor transit options.

Like many other parts of the region, Central Nassau was sharply divided by race and income. For example, the Garden City and Hempstead’s school districts, despite being in direct proximity, were among the most segregated in the region, a reflection of the segregated housing of the time. Hempstead public schools were 96 percent black and Hispanic; Garden City public schools, 90 percent white.

Most public transportation consisted of either slow and unreliable local buses, or infrequent heavy rail access via the LIRR to New York City, which was noisy and ran almost exclusively through residential neighborhoods. Traveling even a short distance between north and south by public transit was very difficult: From the West Hempstead LIRR station to the Garden City LIRR station directly to its north took only five minutes by car; yet public transportation required either two buses and a ten minute walk, or a rail transfer through Queens.

Change began when Nassau County, the Town of Hempstead and the Long Island Rail Road agreed on a plan to develop the Hub to provide affordable housing, commercial office space, and entertainment options, as well as a new transit link that built on decades of analysis by local planners.

The planning process was made easier through greater public engagement and an effort by officials to address concerns about traffic and schools. Leaders committed to focus on schools, adding art, after-school, science and language programs that provided more options for a more diverse student body at each school. Performance was closely monitored to ensure all schools continually improved. Spurred by state incentives, school districts began to collaborate with shared transportation, academic programs and magnet schools. This eventually led school district to merge into larger ones, resulting in more integrated, high-performance schools.

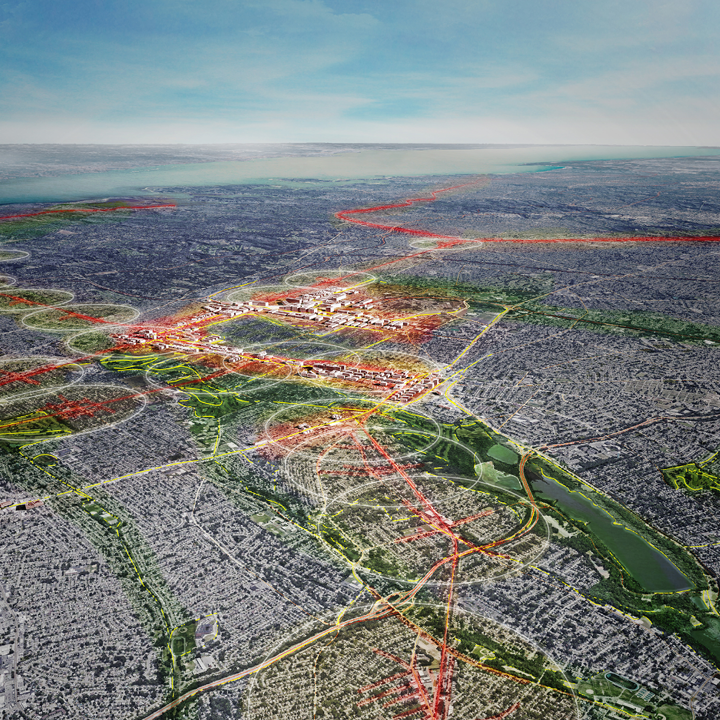

The area had many transportation assets, but they were underutilized. The two least-used branches of the Long Island Rail, the West Hempstead and Oyster Bay branches, were reconfigured as a north/south rapid transit line, connecting through Hempstead and Garden City but retaining their frequent links to Manhattan. An extension to the Nassau Hub was added by utilizing a disused rail right-of-way for part of the route. Communities on the north and south shores now had easy access to the jobs, services, universities and entertainment in Downtown Hempstead, Garden City, and the Nassau Hub. Residents of central Nassau and the south shore were able to easily visit Oyster Bay, the Nassau Museum of Art and two nature preserves on the Oyster Bay line. In addition to better transportation options, the surrounding communities saw a major quality-of-life improvement as the conversion from heavy rail to quieter and low-emitting rapid transit significantly reduced noise.

This transit connection also helped downtown Hempstead and Garden City become a vibrant, walkable corridor with new shops, restaurants, and pedestrian and streetscape improvements including better lighting, more trees, and safer crossings. More walkable areas opened up 22 percent of the land area formerly used for surface parking for new homes, shops, offices, parks, and public facilities like libraries, schools and senior centers.

Another benefit was social integration. In addition to the regional school districts, mixed-use, mixed-income development helped provide affordable homes and more shops and restaurants throughout the corridor from Mineola through Garden City, to Hempstead and West Hempstead. Affordable homes attracted young families, which in turn brought new businesses and investment. And because the new development focused not only on housing but also on expanding civic and commercial space, the area’s anchor institutions –museums, universities and hospitals – were able to grow as well and contribute more to the larger community.

New rapid transit lines gave more people easier access to jobs, nature, and educational, cultural, and recreational opportunities, and the reduced noise and pollution improved life in the surrounding residential neighborhoods. Better streetscapes improved safety and made walking more enjoyable. Transitioning to regional school districts saved money and improved education. The improved transit connections, access to affordable housing, and mixed-income development allowed people of all ages and backgrounds to live in an attractive suburb with complete neighborhoods and a strong sense of community.